After using a fairly large, mature language for a reasonable period of time, finding peculiarities in the language or its libraries is guaranteed to happen. However, given its history, I have to say C++ definitely allows for some of the strangest peculiarities in its syntax. Below I list three that are my favorite.

Ternaries Returning lvalues

You might be familiar with ternaries as condition ? do something : do something else, and they become quite useful in comparison to the standard if-else. However, if you've dealt with ternaries a lot, you might have noticed that ternaries also return lvalues/rvalues. Now, as the name suggests, you can assign to lvalues (lvalues are often referred to as locator values). So something like this is possible:

std::string x = "foo", y = "bar";

std::cout << "Before Ternary! ";

// prints x: foo, y: bar

std::cout << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

// Use the lvalue from ternary for assignment

(1 == 1 ? x : y) = "I changed";

(1 != 1 ? x : y) = "I also changed";

std::cout << "After Ternary! ";

// prints x: I changed, y: I also changed

std::cout << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

Although it makes sense, it’s really daunting; I can attest to never seeing it in the wild.

Commutative Bracket Operator

An interesting fact about the C++ bracket operator: it's simply pointer arithmetic. Writing array[42] is actually the same as writing *(array + 42), and thinking in terms of x86/64 assembly, this makes sense! It's simply an indexed addressing mode, a base (the beginning location of array) followed by an offset (42). If this doesn't make sense, that's okay. We'll discuss the implications without any need for assembly programming.

So we can do something like *(array + 42), which is interesting, but we can do better. We know addition to be commutative, so wouldn't saying *(42 + array) be the same? Indeed it is, and by transitivity, array[42] is exactly the same as 42[array]. The following is a more concrete example.

std::string array[50];

42[array] = "answer";

// prints 42 is the answer

std::cout << "42 is the " << array[42] << ".";

Zero Width Space Identifiers

This one has the least to say, and could cause the most damage. The C++ standard allows for hidden white space in identifiers (i.e. variable names, method/property names, class names, etc.). So this makes the following possible.

int number = 1;

int number = 2;

int number = 3;

std::cout << number << std::endl; // prints 1

std::cout << number << std::endl; // prints 2

std::cout << number << std::endl; // prints 3

Using \u as a proxy for a hidden whitespace character, the above code can be rewritten as:

int n\uumber = 1;

int nu\umber = 2;

int num\uber = 3;

std::cout << n\uumber << std::endl; // prints 1

std::cout << nu\umber << std::endl; // prints 2

std::cout << num\uber << std::endl; // prints 3

So if you’re feeling like watching the world burn, this would be the way to go.

One of the most frustrating things to deal with is the trailing space. Trailing spaces are such a pain because

- They can screw up string literals

- They can break expectations in a text editor (i.e. jumping to a new line or the end of the line)

- They can actually break programming languages

- They are just unflattering

However, in Vim, it takes one autocmd to alleviate this.

augroup spaces

autocmd!

autocmd BufWritePre \* %s/s+$//e

augroup END

On every buffer save substitute spaces at the end of the line with nothing. Easy!

Mercedes-Benz NTG5 STAR2

Fully integrated high-end multimedia system with 6-disc DVD changer, hard-drive navigation system, internet browser, telephony plus DVD video and Music Register, shown on high-resolution 21.3 cm colour TFT display.

The NTG Star2 is a mid-2010s Mercedes-Benz in‑car navigation/infotainment system (part of the COMAND/Audio20 series). In practice it was the NTG5‑generation system used in models like the W205 C‑Class, W222 S‑Class, GLC, etc. For audio and navigation it typically used the standard 7″ (17.8 cm) TFT display and console controller. Importantly, NTG Star2 used Garmin’s “Map Pilot” technology for GPS navigation in Audio20-equipped cars – inserting a Garmin SD‑card lets the Audio20 unit run 3D maps and routing. (The COMAND head unit itself was Mercedes-made, but Garmin supplied the map/database software.)

NTG Star2 debuted around 2014–2015 as the successor to the NTG4.5 COMAND system. Mercedes introduced it on new models (for example, the 2015–2020 C‑Class W205 and later E‑Class and GLC) as COMAND Online (NTG5) hardware. These NTG5/Star2 units featured a built‑in hard drive for media and optional CD/DVD storage. Around 2018–2019 Mercedes began updating Star2 to a new software version called “Star1” (this was essentially a software revision to enable features like Apple CarPlay). As one forum noted, “my new [head unit] is called NTG Star1 and CarPlay works – the old one was NTG Star2”. (In other words, Star2 was the original NTG5 software on older Audio20 hardware; Star1 was the newer update with smartphone integration.)

Today NTG Star2 systems remain supported through Mercedes accessories and parts. Mercedes still sells Garmin Map Pilot SD navigation cards and software updates for NTG5/Star2 systems. For vehicles that came with NTG Star2, a dealer or owner can purchase official updates (e.g. Europe 2020/2021 map packs) for the Garmin Map Pilot. Mercedes also offered an accessory COMAND Online head unit upgrade with DVD changer – a high-end multimedia unit with a 6‑disc changer and hard‑drive nav that replaces the original unit. In short, the NTG Star2 system remains available on its original models (C‑Class, S‑Class, etc.) and can be serviced or upgraded using genuine Mercedes parts (for example, the COMAND Online unit with DVD changer or Garmin Map Pilot module).

While Mercedes-Benz designed the NTG Star2 hardware and user interface, Garmin’s involvement was confined to the navigation content. On Audio20/NTG5 Star2 cars, Garmin supplied the Map Pilot navigation module (SD card and software) that plugs into the Mercedes system. There is no ongoing Garmin development of NTG Star2 itself – Garmin’s input was the map database and guidance engine. All system updates (DVD/DVD changer upgrades or map updates) are handled through Mercedes-Benz parts (including Garmin-branded map cards sold by Mercedes).

Since reading about its faults in The Not So Short Introduction to LaTeX (highly recommended read), I've avidly stayed away from eqnarray. However, I don't think the book conveys the ideas as well as it should. Its suggestion was IEEEeqnarray, as opposed to the classically recommended align. This article from the TeX Users Group conveys them more eloquently and provides better alternatives.

The most frustrating thing about compiling LaTeX in a terminal is the wall of text that gets written to stdout. An easy solution would be piping to /dev/null—except then you wouldn't be able to get error messages (even if you only pipe stdout to /dev/null and keep stderr). So, I made a solution that handles compiling by piping error messages to less. The syntax latexerr FILENAME will compile the file. Passing --clean will delete temporary LaTeX files.

#!/bin/bash

# USAGE: ./script FILE --clean --glossary

extensions_to_delete=(\

gz fls fdb_latexmk blg bbl log\

aux out nav toc snm glg glo xdy

)

compile_and_open() {

argument="$1"

auxname="${argument%.tex}.aux"

errors=$(pdflatex -shell-escape \

-interaction=nonstopmode \

-file-line-error "$argument" | \

grep ".*:[0-9]*:.*")

if [[ -n $errors ]]; then

echo "$1 Errors Detected"

echo "$errors" | less

else

open_file $1

echo "$1 Compile Successful"

fi

}

open_file() {

filename=`echo "$1" | cut -d'.' -f1`

open "$filename.pdf"

echo "$filename Opened"

}

# http://tex.stackexchange.com/questions/6845/compile-latex-with-bibtex-and-glossaries

glossary() {

compile $1

makeglossaries $1

compile $1

compile $1

}

clean() {

for file in $(dirname $1)/*; do

filename=$(basename "$file")

extension="${filename##*.}"

filename="${filename%.*}"

for bad_extensions in "${extensions_to_delete[@]}" ; do

if [[ $bad_extensions = $extension ]]; then

rm $file

echo "$file Deleted"

fi

done

done

}

main() {

compile_and_open $1

if [ "$3" = "--glossary" ]; then

glossary $1

fi

if [ "$2" = "--clean" ]; then

clean $1

fi

}

main "$@"

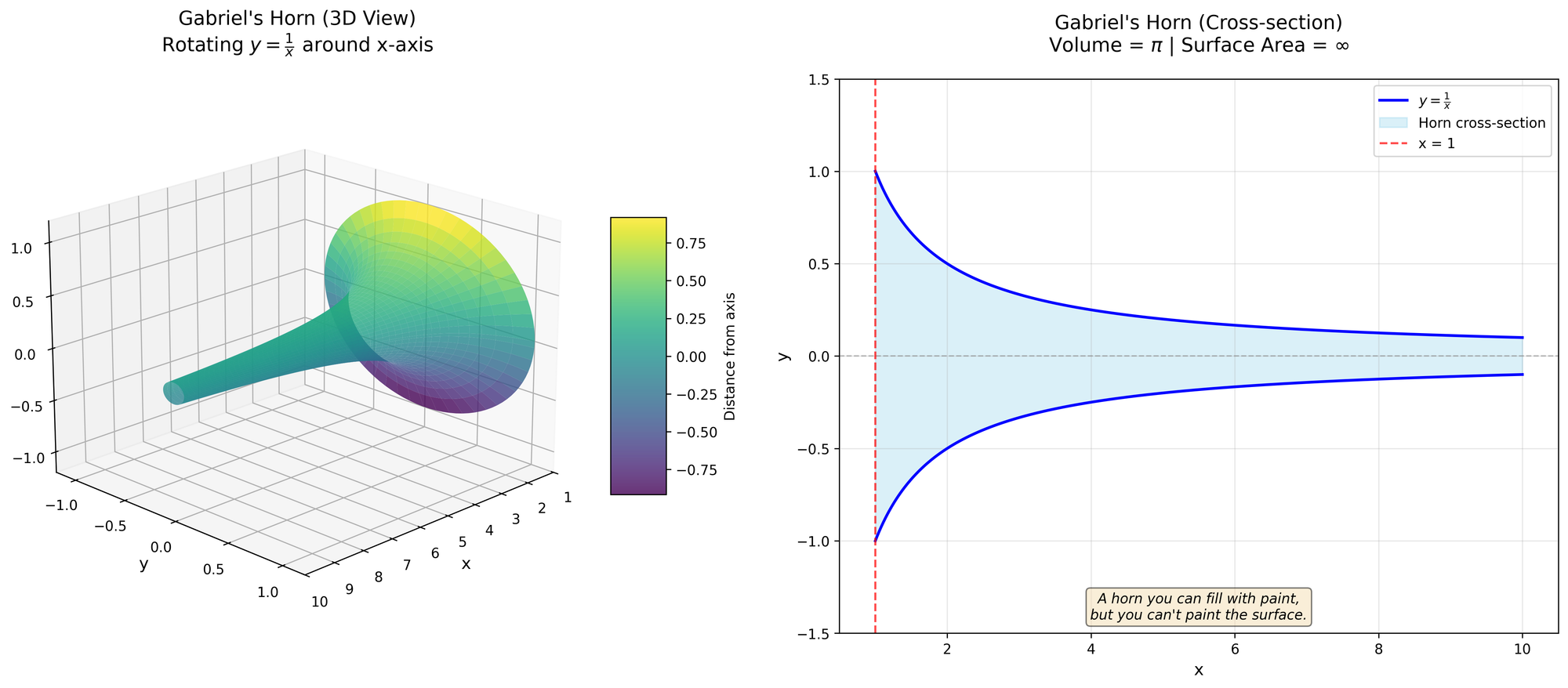

Painting Gabriel’s Horn

A horn you can fill with paint, but you can't paint the surface.

Mathematics is full of wonderful things, but nothing strikes me as more wonderful—or more unintuitive—than Gabriel's Horn.

Here's how it works: take the function $y = \frac{1}{x}$ where $x \in \mathbb{R}^+, 1 \leq x \leq \infty$, and rotate it around the $x$ axis. Not too hard to picture—it looks like a horn. But here's where it gets weird.

Let's calculate the volume. Using solids of revolution, we can show:

$$

V = \pi \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{1}{x^2} dx = \pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} ( 1 - \frac{1}{t} ) = \pi

$$

Simple, elegant. The volume is exactly $\pi$. Now let's check the surface area.

We know the general definition of arc length is $\int _a ^b \sqrt{1 + f'(x)^2}$. Combining this with our solids of revolution gives us:

$$

A = 2\pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{1}{x} \sqrt{1 + \left( -\frac{1}{x^2} \right)^2 } dx

$$

This integral isn't trivial, but there's a trick. Take the simpler integral $$2\pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{dx}{x}$$ instead. This will always be less than or equal to our original integral (we dropped the $\sqrt{1 + (-\frac{1}{x2})2}$ term, which is always ≥ 1). Evaluating this simpler integral:

$$

A \geq 2\pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{dx}{x} \implies A \geq \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} 2\pi \ln(t)

$$

Wait. It diverges. The volume is $V = \pi$, but the surface area is $A \geq \infty$. This isn't a mistake—the math checks out. And that's simply wonderful.

A horn you can fill with paint, but you can't paint the surface.

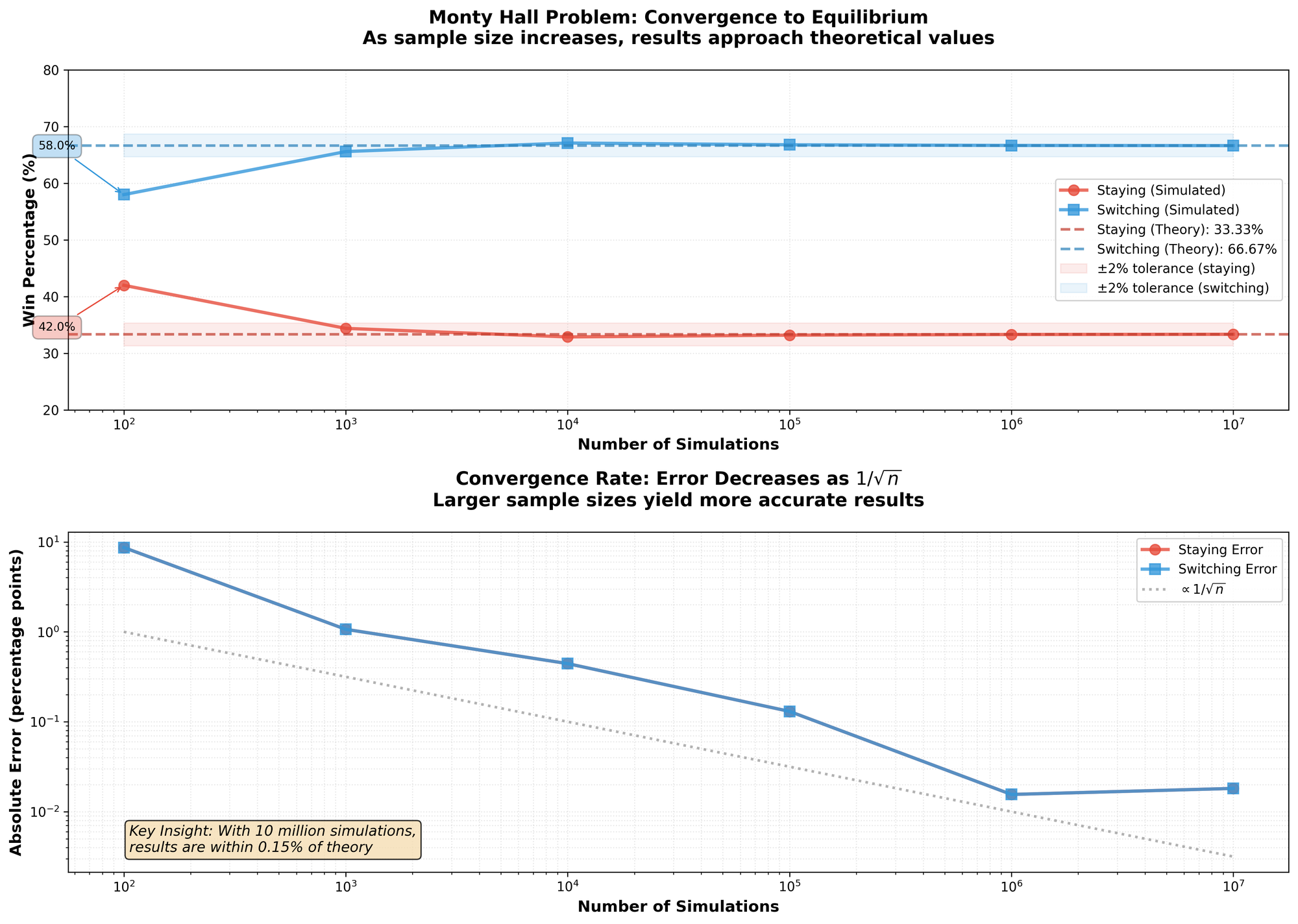

The Monty Hall Problem

You've seen it in movies or read about it in books: the Monty Hall Problem. Here's how it works: you're on a game show. There are three doors—behind one is a prize, behind the other two is nothing but disappointment. You pick a door. The host, Monty Hall, opens one of the other doors and reveals there's no prize behind it. Keeping the other two doors closed, he asks if you'd like to switch your choice or stick with your original pick. What should you do? Ben Campbell has a solution.

You mean to tell me that switching mid-game—an offer from the man who set up all the doors and prizes—gives me better odds of winning? How is this possible? Seems a bit counterintuitive. Seems almost wrong. Fortunately, we can test this with a simple program.

import Darwin // for arc4random_uniform

func random(from from: Int, to: Int,

except: Array<Int>? = nil) -> Int {

// Produce bounds, +1 to make inclusive

let number = Int(arc4random_uniform(UInt32(to - from + 1))) + from

if except != nil && except?.indexOf(number) != nil {

// Recursively call until we find a valid number

return random(from: from, to: to, except: except)

}

return number

}

// Returns if you won when you stayed and switched, respectively

func montyHall(doors: Int) -> (Bool, Bool) {

let originalDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors)

let correctDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors)

// The door the host reveals

let revealedDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors,

except: [correctDoor, originalDoor])

// If you switched, this would be your new door

let switchedDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors,

except: [revealedDoor, originalDoor])

return (originalDoor == correctDoor, switchedDoor == correctDoor)

}

let testValues = [100, 1_000, 10_000, 100_000,

1_000_000, 10_000_000]

let actualNumberOfDoors = 3

for value in testValues {

var stayingCounter = 0, switchingCounter = 0

for _ in 0...value {

let (stayedWon, switchedWon) = montyHall(actualNumberOfDoors)

if stayedWon { stayingCounter += 1 }

if switchedWon { switchingCounter += 1 }

}

let output = "Test Case: \(value). " +

"Staying Won: \(stayingCounter), " +

"Switching Won: \(switchingCounter)"

print(output)

}

There's no tricks in the code. No gimmicks. So, the results?

| Input | Staying Won | Switching Won |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 42 | 58 |

| 1000 | 344 | 656 |

| 10000 | 3289 | 6711 |

| 100000 | 33203 | 66797 |

| 1000000 | 333178 | 666822 |

| 10000000 | 3335146 | 6664854 |

It appears that Ben[1] was right. Taking the limit as the input gets higher, switching won roughly $66%$ of the time—compare that to the original $33%$ you got before you were given the option to switch doors. So, how is this possible? I'll explain.

For simplicity, suppose the prize is behind door A out of doors A, B, C. The argument can be made for any initial door, but A makes it easier. At this point, you have a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of picking the prize no matter what you pick. If you pick door A, the door which contains the prize, the host will definitely want you to change so he will offer you either door B or C. Now suppose you choose a door without the prize, either door B or C. The host has no choice but to eliminate the door without the prize. Meaning if you switch, you have the winning door.

So, why $66%$? Computationally, if you always switch and you picked the wrong door initially, your switch will win every time. There are two incorrect choices out of three, meaning $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time you will win.

You've just had your first lesson in conditional probability.

- 21 main character, played by Jim Sturgess ↩︎

Apps of 2014

My favorites from a landmark year.

As this is my first year of writing about apps, I wanted to do something this Christmas: thank the apps and writers that made this year such a special year. I have broken down my favorite iOS and OS X apps and articles.

As there are many great apps this year, it is impossible to catalog them all. So I have decided to break it down to my personal favorite, runner-up, and a selected few honorable mentions.

Congratulations to everyone who made the list, and I hope to see you all next year with the wonderful things you create in the coming year.

iOS

This was the second biggest year for iOS developers, runner-up to the introduction of the App Store. iOS 8 expanded the capabilities of what the iPhone and iPad could do. Thanks to extensions and continuity, iOS has never been more powerful. A more powerful iOS means more powerful apps.

With so many apps, there are equally so many opportunities. Applications that were never possible before are now on the App Store—not to mention the Today View widgets, keyboards, extensions, and so much more.

This is why the runner-up Workflow is such an intriguing, new app; it builds on the power and functionality of iOS. However, the winner this year is Overcast.

Winner: Overcast

Among the podcast renaissance, Overcast shines as the most notable choice for iOS enthusiasts. There are many features that make Overcast shine, apart from the developer and Accidental Tech Podcast host Marco Arment. The favorite features: Smart Speed and Voice Boost.

Smart Speed is without a doubt my favorite feature in any podcasting app. It builds upon the current speed setting, and skips pauses and gaps in audio to save minutes or hours a week. The best part of it all? The fact that I never notice the boost in speed. Sometimes I don't believe that Smart Speed is on, only to check and realize it's on 1.2x or even 1.3x speed. Furthermore, the Voice Boost works just as the name suggests, boosting the voice and nothing more. With the suppressed iPhone speaker, sometimes it is impossible to hear podcasts through the background noise when I'm doing dishes, laundry, or just dealing with outside noise. The accuracy of Smart Speed and Voice Boost is unmatched, and quite frankly I don't think there is any podcast app that is comparable to it.

In addition to Smart Speed and Voice Boost, Overcast also features intuitive playlists, a customary and elegant iOS 8 appeal, a huge directory of podcasts, Twitter recommendations, and curated playlists. There are other things that Overcast doesn't do that simply delight me: it never pesters you to buy the in-app purchase if you haven't purchased it, never nags for a review, and the decision to not incorporate top lists. Plainly, everything about Overcast delights me.

Overcast is free on the App Store, with a $4.99 in-app purchase to "unlock everything"—Smart Speed, Voice Boost, unlimited playlists, and more.

Runner-Up: Workflow

The newly-released app by the team at DeskConnect is an exceptional example of iOS automation. With many powerful actions, variables, and automation tools, Workflow is amongst the most powerful apps within the App Store. The possibilities are almost endless.

Of the many things possible via Workflow, some of the workflows I have forked and created from the internet can do things never before possible on iOS, such as:

- Markdownifying webpages

- Cross-posting images to Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram

- Annotating and deleting screenshots

- Getting all my calendar events and sharing availability

- Getting a random dining option

Though it is most certainly a power-user app, the interface is simplistic enough that just about any user can unlock its full capacity.

Workflow is $2.99 on the App Store.

Honorable Mentions

- 1Password: my go-to password manager, an app that I use religiously. With an encrypted vault, powerful password generator, and Launch Center Pro capability, I could not think of an app that deserves a more honorable mention.

- Launch Center Pro: an application that takes advantage of iOS's URL schemes, adding the potential to create powerful shortcuts and workflows.

- Editorial: the most powerful text editor on iOS. Editorial supports Markdown, plain text, TextExpander, custom workflows, and so much more.

- Evernote: my central note-taking app. On iOS, I use the Evernote share sheet more than any other, simply because it's so simple yet powerful.

- Tweetbot: my Twitter experience. I use Tweetbot over Twitter simply because of the iCloud syncing, no advertisements, more powerful mute filters, better font options, and better appeal.

OS X

I took a different approach than what most people are doing—instead of showcasing apps that took full advantage of Yosemite, I wanted to show off the most-used applications on my Mac.

Granted, Yosemite did bring a visual redesign that brought a downright beautiful experience to the Mac; however, this was not the only change to the Mac. Continuity brought about a more seamless Mac experience, making things like Handoff and Text Message Forwarding possible. Many other little things got an upgrade, like Mail, Notification Center, and Spotlight.

Ironically, even though Spotlight got a major improvement, this year's winner is Alfred 2, with runner-up being 1Password.

Winner: Alfred 2

As this is my first year doing favorite apps, what better app to introduce than one I use most: Alfred. Alfred was amongst the first set of apps I downloaded on my first MacBook—it was the best decision I have ever made. Since January 27, 2014, I have used Alfred 15,867 times, averaging 49.0 times per day. There is no app that comes to mind that I have used nearly as much.

After the Yosemite reveal, Spotlight was revamped to have more of an Alfred appeal; however, Spotlight cannot replace Alfred (and will unlikely ever replace Alfred). Granted, Spotlight and Alfred do similar things: they launch files, can give directions and addresses, provide contact information, and offer many shortcuts that save me hours a week.

So why is Alfred so important to me? Simple: workflows and expanded functionality. I am not confined to the default features of Spotlight—I can make or fork workflows. Instead of just launching apps, I can also kill and quit apps. If I have an app to look up, I don't have to search via the Mac App Store. That would be tiring. Instead, I search via Alfred. Find Evernote notes? There's a workflow for that. Netflix search? Workflow for that. The possibilities are only constricted by my imagination.

Alfred 2 is free via their website, and the Powerpack price varies.

Runner-Up: 1Password

1Password is an application that I use religiously—on iOS and OS X both. With a visual overhaul to match Yosemite's flatter and translucent design, 1Password makes password management actually enjoyable.

1Password brings 21st-century peace of mind in an internet filled with malicious intentions. Being the powerhouse of security, password storage, and password management that 1Password is, you can sleep safe and sound knowing your passwords won't be compromised.

1Password is $34.99 on the Mac App Store or the AgileBits website.

Honorable Mentions

- TextExpander: saves time by expanding short abbreviations into frequently-used text.

- OmniFocus: my choice for task management. OmniFocus is an unparalleled task manager that is simply unmatched by any other application on OS X.

- iStat Menus: a utility that quickly displays the statistics of my MacBook. Currently, I have many items enabled: CPU history and CPU cores, memory used/free, disk activity, bandwidth and bandwidth history, sensors, and time. Everything I need quick access to is a glance away, and more in-depth statistics are a click away.

- Bartender: with so many iStat Menus enabled, there is no space for menu items—my solution is Bartender. Bartender has all of my menu items outside of iStat Menus, including Backblaze, Dropbox, TextExpander, and 1Password.

- Yoink: after dragging and dropping time and time again, you might realize how frustrating it can be sometimes; Yoink brings a solution. Every time you drag something, Yoink slides a little window to store that file in—and keeps it there until you're ready to drop it somewhere. Simple yet so powerful.

Merry Christmas!