Code

If you've ever written a shell script, you'd top your script with your interpreter of choice (i.e. #!/bin/python or #!/bin/bash). What you might not know is that rm is also a valid interpreter. Take the following script.

#!/bin/rm

echo "Hello, world"

It would simply interpret to be removed. Useful? No. Hilarious? Yes.

Arguably the first (and most successful) problem solver we know of is Evolution. Humans (along with other species) all share a common problem: becoming the best at surviving our environment.

Just as Darwinian finches evolved their beaks to survive different parts of the Galápagos Islands, we too evolved to survive different parts of the world. And we can program a computer to do the same.

Evolution inspired a whole generation of problem solving, commonly known as Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs). EAs have been known for solving (or, approximating) solutions to borderline unsolvable problems. And, just as the mechanics of evolution are not that difficult, the mechanics of EAs are just the same.

Today, we will build an Evolutionary Algorithm from the ground-up.

An Introduction

Before we proceed with implementation or an in-depth discussion, first we wish to tackle three questions: what is an Evolutionary Algorithm, what does an Evolutionary Algorithm look like, and what problems can Evolutionary Algorithms solve.

What Is An Evolutionary Algorithm?

An Evolutionary Algorithm is generic, population-based optimization algorithm that generates solution via biological operators. That is quite a mouthful, so let’s break it up.

Population-based. All Evolutionary Algorithms start by creating a population of random individuals. These individuals are just like an individual in nature: there is a genotype (the genes that make up an individual) and a phenotype (the result of the genotype interacting with the environment). In EAs, they would be defined as follows:

- Genotype The representation of the solution.

- Phenotype The solution itself.

Because it’s a little confusing to think of it this way, it’s often better to think about it in terms of a genotype space and a phenotype space.

- Genotype Space The space of all possible combinations of genes.

- Phenotype Space The space of all possible solutions.

Don’t worry if this doesn’t make sense, we’ll touch on it later.

Optimization Algorithm. Evolution is an optimization algorithm. Given an environment, it will try to optimize an individual for that environment with some fitness metric. Evolutionary Algorithms operate the same way.

Given an individual, it will try to optimize it. We do not use a literal environment, but still use a fitness metric. The fitness metric is simply a function that takes in the genotype of the individual, and outputs a value that is proportional to how good a solution is.

Because fitness metrics are proportional to how good a solution is, this implies a very important condition for our phenotype space: it’s a gradient.

Biological operators. Evolutionary Algorithms are inspired by biology and evolution. Just as biology has operators to generate new individuals, so do Evolutionary Algorithms. More on that later.

Generic. Evolutionary Algorithms are generic. When a framework has been introduced, it can be reused on an individual basis (provided it has the appropriate crossover and mutator operators).

What Does An Evolutionary Algorithm Look Like?

The pseudocode for an Evolutionary Algorithm is one we might expect evolution to have, generate a random population, generate offspring, and let survival of the fittest do its job. And so it does:

BEGIN

INITIALISE population with random solutions

WHILE ( TERMINATION CONDITION is satisfied ) DO

SELECT parents

RECOMBINE pairs of parents

MUTATE the resulting offspring

EVALUATE new candidates

SELECT individuals for the next generation

OD

END

What Problems Can Evolutionary Algorithms Solve?

Evolutionary Algorithms can solve any problem that has a genotype that can fit within our framework:

- The genotype can have a crossover operator.

- The genotype can have a mutator operator.

- The genotype can map to a definite fitness function.

Again, the fitness should be proportional to how good a solution is. If the fitness function $f(x)$ is bounded by $0 \leq f(x) \leq 100$, 0 should be the worst solution or no solution, and $100$ should be the best solution (or vice versa, for inverted fitnesses).

Implementing An Evolutionary Algorithm

We will be implementing a special class of Evolutionary Algorithm, referred to as a (μ + λ)-Evolutionary Strategy. The name is not important, but μ and λ will be; we will come back to them shortly.

For the purposes of our discussion, we are going to consider a sample problem: a deciphering program. The premise of the problem is such.

- There is a string of characters (without spaces) hidden away that, after set, is inaccessible.

- There are two ways to retrieve data about the hidden message:

- Get the length of the string.

- Given a string, the problem will output how many characters match within the two strings.

The secret message would look as follows:

class SecretMessage:

def __init__(self, message):

"""Initialize a Secret Message object.

:message (str): The secret message to hide.

"""

self.__message = message

def letters_match(self, message):

"""Determine how many characters match the secret message.

Note:

The message length and the secret message length must be

the same length (accessed via the length property).

:message (str): The message to compare the secret message to.

:returns (int): The number of characters matched.

"""

return sum(self.__message[char] == message[char]

for char in range(len(message)))

@property

def length(self):

"""Get the length of the secret message.

:returns (int): The length of the secret message.

"""

return len(self.__message)

Not too complicated.

An Individual

In Evolutionary Algorithms, an individual is simply a candidate solution. An individual has a genotype (the representation) and operators (Crossover, Mutation, and Fitness) that act on the genotype. We will discuss them more extensively below.

The Genotype

As aforementioned, a genotype is the representation of an individual. Just as DNA does for humans, knowing the genotype can give you all the information one might need to determine the characteristics of an individual.

Because a genotype must be acted upon a crossover and mutation operator, there are few common choices for genotypes:

- Vectors[1]. A vector is common because crossover is trivial, take elements from the two genotypes to create a new individual. Mutation is also trivial, pick random elements in vector, and mutate them. Often, for a complex enough individual, a vector of bits is used[2].

- Matrices. Same as a vector, but with multiple dimensions.

- Float-Point or Real Numbers. This one is tricky, but commonly used. There are a plethora of ways to recombine two numbers: average of the two numbers, bit manipulation, binary encoding crossover. Same can be said for mutation: adding a random value to the number, bit manipulation with a random value, or bit flipping in binary encoding. It should be noted that some of these introduce biases, and one should account for them.

- Trees. Some problems can be easily broken down into trees (like an entire programming language can be broken down into a parse tree). Crossover is trivial, swap a random subtree with another. Mutation, however, is often not used; this is because the crossover itself acts as a mutation operator.

Next, our genotype must be initialized to some random values. Our initial population is seeded with said randomly-generated individuals, and with a good distribution, they will cover a large portion of the genotype space.

Keeping all this in mind, let us think about the representation of our problem. A string is nothing more than a vector of characters, so using the first bullet point, we are given our operators pretty easily.

Here’s what our genotype would look like:

class Individual:

message = SecretMessage("")

def __init__(self):

"""Initialize an Individual object.

Note:

Individual.message should be initialized first.

"""

length = Individual.message.length

characters = [choice(ascii_letters) for _ in range(length)]

self.genotype = "".join(characters)

Crossover, Mutation, and Fitness

As aforementioned, to fit within an Evolutionary Algorithm framework, a genotype must be created with crossover, mutator, and fitness operators. Although we have covered said operators, we will formalize them here.

- Crossover. A crossover operator simply takes in two genotypes, and produces a genotype that is a mixture of the two. The crossover can be uniform (random elements from both genotypes are taken), 1-point (take a pivot position between two points, the left half is one genotype, and the right half another), and $N$-point (same as 1-point but with multiple pivot positions).

- Mutator. A mutator operator takes random values within the genotype and changes them to a random values. There is a mutation rate that is associated with all genotypes, we call it $p$. $p$ is bounded such that $0 \leq p \leq 1.0$, where $p$ is the percentage of the genotype that gets mutated. Careful to limit this value, however; too high $p$ can result in just a random search.

- Fitness. The fitness operator simply takes in a genotype, and outputs a numerical value proportional to how good a candidate solution is. Fitness has no limits, and can be inverted (i.e., a smaller fitness is better).

For the purposes of our program, we are going to have the following operators: crossover will be uniform, mutation will be a fixed number of mutating characters, and fitness will be a percentage of the characters matched.

class Individual

...

@property

def fitness(self):

"""Get the fitness of an individual. This is done via a

percentage of how many characters in the genotype match the

actual message.

:return (float): The fitness of an individual.

"""

matches = Individual.message.letters_match(self.genotype)

return 100 * matches / Individual.message.length

@staticmethod

def mutate(individual, rate):

"""Mutation operator --- mutate an individual with a

specified rate. This is done via a uniform random mutation,

by selecting random genes and swapping them.

Note:

rate should be a floating point number (0.0 < rate < 1.0).

:individual (Individual): The individual to mutate.

:rate (float): The rate at which to mutate the genotype.

"""

num_to_mutate = int(rate * individual.message.length)

# Strings are immutable, we have to use a list

genotype_list = list(individual.genotype)

for _ in range(num_to_mutate):

char_to_mutate = choice(range(individual.message.length))

genotype_list[char_to_mutate] = choice(ascii_letters)

individual.genotype = "".join(genotype_list)

@staticmethod

def recombine(parent_one, parent_two):

"""Recombination operator --- combine two individuals to

generate an offspring.

:parent_one (Individual): The first parent.

:parent_two (Individual): The second parent.

:returns (Individual): The combination of the two parents.

"""

new_genotype = ""

for gene_one, gene_two in zip(parent_one.genotype, parent_two.genotype):

gene = choice([gene_one, gene_two])

new_genotype += gene

individual = Individual()

individual.genotype = new_genotype

return individual

A Population

Now that we have an Individual, we must create a Population. The Population holds the candidate solutions, creates new offspring, and determine which are to propagate into further generations.

μ And λ

Remember when we mentioned that μ and λ would be important in our Evolutionary Algorithm? Well, now here they come into play. μ And λ are defined as follows:

- μ: The population size.

- λ: The number of offspring to create.

Although these are simple constants, they can have a drastic impact on an Evolutionary Algorithm. For example, a Population size of 1,000 might find a solution in much fewer generations than 100, but will take longer to process. It has been experimentally shown that a good proportion between the two is:

$$

λ / μ \approx 6

$$

However, this is tested for a large class of problems, and a particular Evolutionary Algorithm could benefit from having different proportions.

For our purposes, we will pick $μ = 100$ and $λ = 15$, a proportion just a little over 6.

class Population:

def __init__(self, μ, λ):

"""Initialize a population of individuals.

:μ (int): The population size.

:λ (int): The offspring size.

"""

self.μ, self.λ = μ, λ

self.individuals = [Individual() for _ in range(self.μ)]

Generating Offspring

Generating offspring is trivial with the framework we imposed on an Individual: pick two random parents, perform a crossover between the two to create a child, mutate said child, and introduce the child back into the population pool.

In code, it would look as follows:

class Population:

...

@staticmethod

def random_parents(population):

"""Get two random parents from a population.

:return (Individual, Individual): Two random parents.

"""

msg_len = population.individuals[0].message.length

split = choice(range(1, msg_len))

parent_one = choice(population.individuals[:split])

parent_two = choice(population.individuals[split:])

return parent_one, parent_two

@staticmethod

def generate_offspring(population):

"""Generate offspring from a Population by picking two random

parents, recombining them, mutating the child, and adding it

to the offspring. The number of offspring is determined by λ.

:population (Population): The population to generate from.

:returns (Population): The offspring (of size λ).

"""

offspring = Population(population.μ, population.λ)

offspring.individuals = []

for _ in range(population.λ):

parent_one, parent_two = Population.random_parents(population)

child = Individual.recombine(parent_one, parent_two)

child.mutate(child, 0.15)

offspring.individuals += [child]

return offspring

Survivor Selection

The last core part of an Evolutionary Algorithm would be survival selection. This puts selective pressure on our candidate solutions, and what ultimately leads to fitter solutions.

Survivor selection picks μ Individuals that would be the best to propagate into the next generation; however, it’s not as easy as picking the fittest μ Individuals. Always picking the μ best Individuals leads to premature convergence, a way of saying we “got a good solution, but not the best solution”. The Evolutionary Algorithm simply did not explore the search space enough to find other, fitter solutions.

There are a number of ways to run a survival selection, one of the most popular being $k$ -tournament selection. $k$ -tournament selection picks $k$ random Individuals from the pool, and selects the fittest Individual from the tournament. It does this μ times, to get the full, new Population. The higher $k$, the higher the selective pressure; however, also the higher chance of premature convergence. The lower $k$, the less of a chance of premature convergence, but also the more the Evolutionary Algorithm starts just randomly searching.

At the bounds, $k = 1$ will always be just a random search, and $k = μ$ will always be choosing the best μ individuals.

We choose $k = 25$, giving less fit solutions a chance to win, but still focusing on the more fit solutions.

@staticmethod

def survival_selection(population):

"""Determine from the population what individuals should not

be killed. This is done via k-tournament selection: generate

a tournament of k random individuals, pick the fittest

individuals, add it to survivors, and remove it from the

original population.

Note:

The population should be of size μ + λ.

The resultant population will be of size μ.

:population (Population): The population to run survival

selection on. Must be of size μ + λ.

:returns (Population): The resultant population after killing

off unfit individuals. Will be of size μ.

"""

new_population = Population(population.μ, population.λ)

new_population.individuals = []

individuals = deepcopy(population.individuals)

for _ in range(population.μ):

tournament = sample(individuals, 25)

victor = max(tournament, key=lambda individual: individual.fitness)

new_population.individuals += [victor]

individuals.remove(victor)

return new_population

The Evolutionary Algorithm

As with the pseudocode in the introduction, this will exactly resemble our Evolutionary Algorithm. Because the Individual and the Population framework is established, it is almost a copy-paste.

class EA:

def __init__(self, μ, λ):

"""Initialize an EA.

:μ (int): The population size.

:λ (int): The offspring size.

"""

self.μ, self.λ = μ, λ

def search(self):

"""Run the genetic algorithm until the fitness reaches 100%.

:returns: The fittest individual.

"""

generation = 1

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

while self.population.fittest.fitness < 100.0:

offspring = Population.generate_offspring(self.population)

self.population.individuals += offspring.individuals

self.population = Population.survival_selection(self.population)

generation += 1

Running An Evolutionary Algorithm

Below, we have an instance of the evolutionary algorithm searching for a solution:

Now, looking at the string “FreneticArray”, it has 13 characters, and seeing as there are 26 letters in the alphabet, double that for lowercase/uppercase letters, our search space was:

$$

\left(2 * 26\right)^{13} \approx 2.0 \times 10^{22}

$$

Huge.

On average, our EA took 29 generations to finish[3]. As each generation had at most 115 individuals, we can conclude on average we had to generate:

$$

29 * 115 = 3335\, \text{solutions}

$$

Much smaller than $2.0 \times 10^{22}$. That is what Evolutionary Algorithms are good for: turning a large search space into a much smaller one.

Although there are much more advanced topics in Evolutionary Algorithms, this is enough start implementing your own. With just the simple operators listed above, a genotype, a search space that has a gradient, many problems can solved with an Evolutionary Algorithm.

One of the most valuable skills I have learned in the past year is undoubtedly LaTeX — so much so that I have moved almost all of my notetaking and document writing to LaTeX or Pandoc.

However, with almost any markup language, I ran into friction: constantly importing headers and defining commands I used in every document. Some commands have become muscle memory. When I got compiler errors every time I forgot to redefine them, I became quite frustrated. So I caved: I made a preamble that I appended to all of my LaTeX docs.

\RequirePackage[l2tabu, orthodox]{nag}

\documentclass[12pt]{article}

\usepackage{amssymb,amsmath,verbatim,graphicx,microtype,units,booktabs}

\usepackage[margin=10pt, font=small, labelfont=bf,

labelsep=endash]{caption}

\usepackage[colorlinks=true, pdfborder={0 0 0}]{hyperref}

\usepackage[utf8]{inputenc}

\usepackage{xcolor}

% Highlight shell or code commands

\newcommand{\shellcmd}[1]{\texttt{\colorbox{gray!30}{#1}}}

% Placeholder for something to do

\newcommand{\todo}[2]{\textbf{\colorbox{red!50}{#1}}{\footnote{#2}}}

% Format a table row to make it more visible

\newcommand{\gray}{\rowcolor[gray]{.9}}

\usepackage[left=1.15in, right=1.15in]{geometry}

\usepackage{titleps}

\newpagestyle{main}{

\setheadrule{.4pt}

\sethead{\sectiontitle}

{}

{Illya Starikov}

}

\pagestyle{main}

% *-------------------- Modify This As Needed --------------------* %

% \usepackage[top=0.5in, bottom=0.5in, left=0.5in, right=0.5in]{geometry}

% \pagestyle{empty}

\title{\todo{Title}{Insert title here.}}

\date{\today}

\author{Illya Starikov}

Then, I took it one step further. I occasionally make practice tests for students in Calculus and Physics, so I decided to make a command that acts as extensions of my preamble for tests.

\usepackage{lastpage,ifthen}

\newboolean{key}

\setboolean{key}{true} % prints questions and answers

% \setboolean{key}{false} % prints questions only

\newcommand{\question}[2]{\item (#1 Points) #2}

\newcommand{\answer}[1]{\ifthenelse{\boolean{key}}{#1}{}}

% This must be filled out

\newcommand{\points}{0} % total number of points for the exam

% Capping score, to offer a point or two bonus

\newcommand{\capped}{0\ }

\newcommand{\difference}{0\ } % the difference of the two

\newcommand{\timeallotted}{0 hour} % duration of the exam

\begin{document}

\section*{\answer{Key}}

Complete the following problems.

In order to receive full credit,

please show all of your work and justify your answers.

You do not need to simplify your answers

unless specifically instructed to do so.

You have \timeallotted.

This is a closed-book, closed-notes exam.

No calculators or other electronic aids will be permitted.

If you are caught cheating, you will receive a zero grade for this exam.

Please check that your copy of this exam contains \pageref{LastPage}

numbered pages and is correctly stapled.

The sum of the max points for all the questions is \points,

but note that the max exam score will be capped at \capped

(i.e., there is \difference bonus point(s),

but you can't score more than 100\%).

Best of luck.

\begin{enumerate}

\question{}{}

\answer{}

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}

Ever wondered how sorting algorithms look in Swift? I did too—so I implemented some. Below you can find the following:

- Bubble Sort

- Selection Sort

- Insertion Sort

- Merge Sort

- Quicksort

As a preface: some of the algorithms use a custom swap function—it is as follows:

extension Array {

mutating func swap(i: Int, _ j: Int) {

(self[i], self[j]) = (self[j], self[i])

}

}

Bubble Sort

func bubbleSort(var unsorted: Array<Int>) -> Array<Int> {

for i in 0..<unsorted.count - 1 {

for j in 0..<unsorted.count - i - 1 {

if unsorted[j] > unsorted[j + 1] {

unsorted.swap(j, j + 1)

}

}

}

return unsorted

}

Selection Sort

func selectionSort(var unsorted: Array<Int>) -> Array<Int> {

for i in 0..<unsorted.count - 1 {

var minimumIndex = i

for j in i + 1 ..< unsorted.count {

if unsorted[j] < unsorted[minimumIndex] {

minimumIndex = j

}

unsorted.swap(minimumIndex, i)

}

}

return unsorted

}

Insertion Sort

func insertionSort(var unsorted: Array<Int>) -> Array<Int> {

for j in 1...unsorted.count - 1 {

let key = unsorted[j];

var i = j - 1

while i >= 0 && unsorted[i] > key {

unsorted[i + 1] = unsorted[i]

i--

}

unsorted[i + 1] = key

}

return unsorted

}

Merge Sort

func merge(leftArray left: Array<Int>,

rightArray right: Array<Int>) -> Array<Int> {

var result = [Int]()

var leftIndex = 0, rightIndex = 0

// Computed property to check if indexes reached end of arrays

var indexesHaveReachedEndOfArrays: Bool {

return leftIndex < left.count && rightIndex < right.count

}

while indexesHaveReachedEndOfArrays {

if left[leftIndex] < right[rightIndex] {

result.append(left[leftIndex])

leftIndex++

}

else if left[leftIndex] > right[rightIndex] {

result.append(right[rightIndex])

rightIndex++

}

else {

result.append(left[leftIndex])

result.append(right[rightIndex])

leftIndex++

rightIndex++

}

}

result += Array(left[leftIndex..<left.count])

result += Array(right[rightIndex..<right.count])

return result

}

func mergesort(unsorted: Array<Int>) -> Array<Int> {

let size = unsorted.count

if size < 2 { return unsorted }

let split = Int(size / 2)

let left = Array(unsorted[0 ..< split])

let right = Array(unsorted[split ..< size])

let sorted = merge(leftArray: mergesort(left),

rightArray: mergesort(right))

return sorted

}

Quick Sort

func quicksort(var unsorted: Array<Int>) -> Array<Int> {

quicksort(&unsorted, firstIndex: 0,

lastIndex: unsorted.count - 1)

return unsorted

}

private func quicksort(inout unsorted: Array<Int>,

firstIndex: Int,

lastIndex: Int) -> Array<Int> {

if firstIndex < lastIndex {

let split = partition(&unsorted, firstIndex: firstIndex,

lastIndex: lastIndex)

quicksort(&unsorted, firstIndex: firstIndex,

lastIndex: split - 1)

quicksort(&unsorted, firstIndex: split + 1,

lastIndex: lastIndex)

}

return unsorted

}

private func partition(inout unsorted: Array<Int>,

firstIndex: Int,

lastIndex: Int) -> Int {

let pivot = unsorted[lastIndex]

var wall = firstIndex

for i in firstIndex ... lastIndex - 1 {

if unsorted[i] <= pivot {

unsorted.swap(wall, i)

wall++

}

}

unsorted.swap(wall, lastIndex)

return wall

}

It’s not so often I come across a problem that works out so beautifully yet requires so many different aspects in competitive programming. One particular problem, courtesy of Kattis, really did impress me.

The problem was House of Cards, and the problem was this (skip for TL;DR at bottom):

Brian and Susan are old friends, and they always dare each other to do reckless things. Recently Brian had the audacity to take the bottom right exit out of their annual maze race, instead of the usual top left one. In order to trump this, Susan needs to think big. She will build a house of cards so big that, should it topple over, the entire country would be buried by cards. It’s going to be huge!

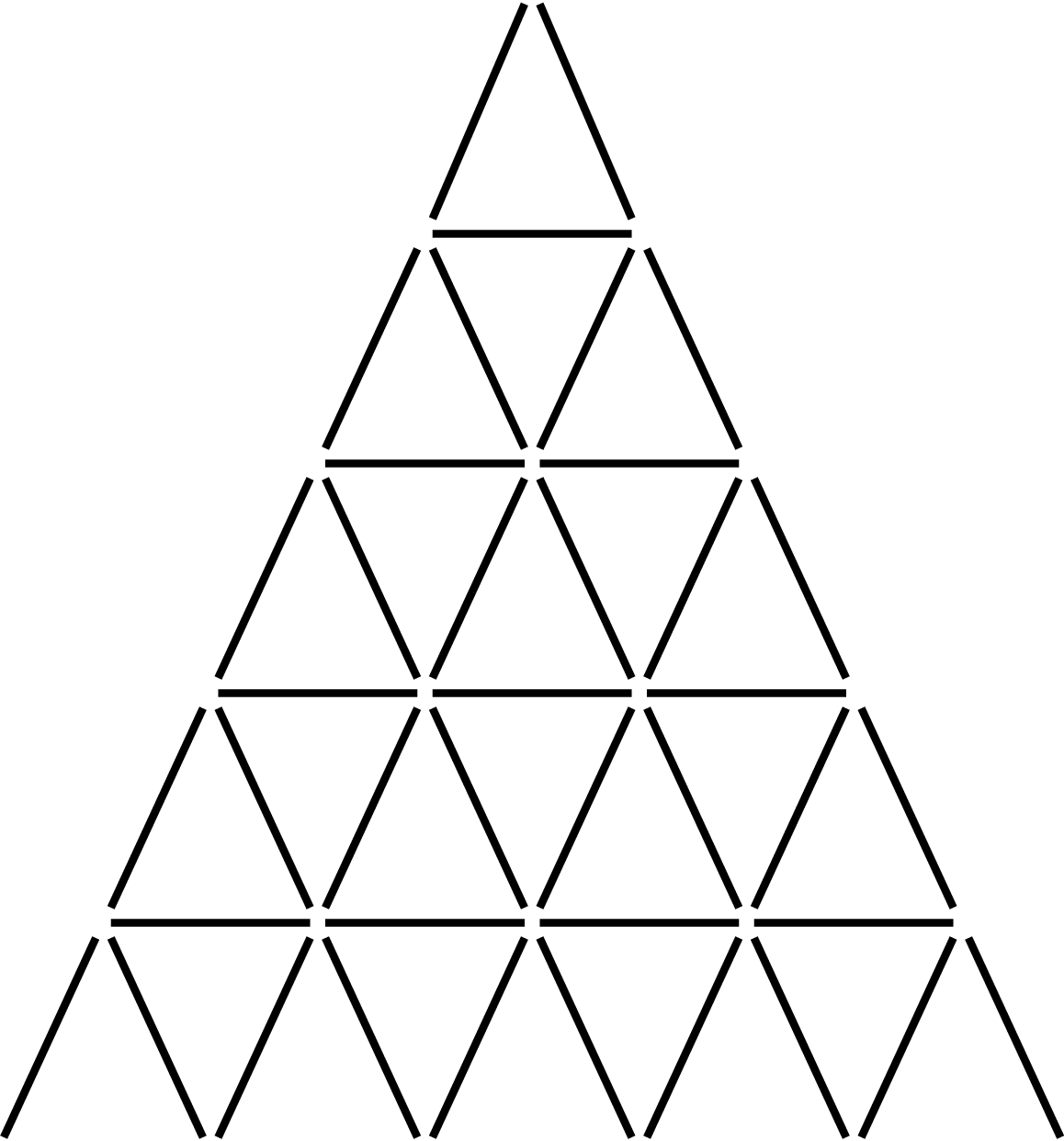

The house will have a triangular shape. The illustration to the right shows a house of height 6 and Figure 1 shows a schematic figure of a house of height 5.

For aesthetic reasons, the cards used to build the tower should feature each of the four suits (clubs, diamonds, hearts, spades) equally often. Depending on the height of the tower, this may or may not be possible. Given a lower bound $h_0$ on the height of the tower, what is the smallest possible height $h \geq h_0$ such that it is possible to build the tower?

TL;DR: Using Figure 1 as a reference, you are given a lower bound on a height for a tower of cards. However, there must be an equal distribution of all four suits: clubs, diamonds, hearts, and spades.

This implies that the number of cards has to be divisible by $4$. Seeing as the input was huge $1 \leq h_0 \leq 10^{1000}$, there was no brute forcing this. So, first thought: turn this into a closed-form series, and solve the series.

Getting the values for the first five heights, I got the following set:

$${2, 7, 15, 26, 40, \ldots}$$

I was able to turn this set into a series quite easily:

$$\sum _{n = 1} ^{h_0} \left(3n - 1\right)$$

This turned into the following equation:

$$\frac{1}{2} h_0(3,h_0 + 1)$$

So, all I had to do was plug $h_0$ into the equation, and increment while the number was not divisible by $4$. Then, I realized how large the input really was. The input size ($1 \times 10^{1000}$) was orders of magnitude larger than what typical large data types would allow ($1.84 \times 10^{19}$).

I realized this couldn't be tested against an intensive data set—since we only calculate one value per test case, the solution doesn't need to be highly optimized. Looking at the formula, I figured the answer would be found within a few increments at most. Keeping this in mind, I decided to use Python. Python can work with arbitrarily large numbers, making it ideal for this situation.

I sat down, hoped for the best, and wrote the following code.

def getNumberOfCards(x):

return (3*pow(x, 2) + x) // 2

height = int(input())

while getNumberOfCards(height) % 4 != 0:

height += 1

print(height)

It worked.

One of the reasons I kept CodeRunner handy was its ability to quickly compile code. With a single click of a button, I could run any of my frequently used languages. It didn’t matter if it was an interpreted or compiled language, so I could virtually run anything, like:

- C/C++

- Python

- Lua

- LaTeX

- Perl

However, in the last few months I started using Vim. Heavily. So much so I was trying to use Vim commands in the CodeRunner buffers. So I decided I wanted to have the functionality, and in Vim-esque fashion, I mapped to my leader key: <leader>r. The mnemonic <leader>run helped me remember the command on the first few tries.

To get the functionality, just add the following to your .vimrc.

function! MakeIfAvailable()

if filereadable("./makefile")

make

elseif (&filetype == "cpp")

execute("!clang++ -std=c++14" + bufname("%"))

execute("!./a.out")

elseif (&filetype == "c")

execute("!clang -std=c11" + bufname("%"))

execute("!./a.out")

elseif (&filetype == "tex")

execute("!xelatex" + bufname("%"))

execute("!open" + expand(%:r))

endif

endfunction

augroup autorun

autocmd!

autocmd FileType c nnoremap <leader>r :call MakeIfAvailable()<cr>

autocmd FileType cpp nnoremap <leader>r :call MakeIfAvailable()<cr>

autocmd FileType tex nnoremap <leader>r :call MakeIfAvailable()<cr>

autocmd FileType python nnoremap <leader>r

\ :exec '!python' shellescape(@%, 1)<cr>

autocmd FileType perl nnoremap <leader>r

\ :exec '!perl' shellescape(@%, 1)<cr>

autocmd FileType sh nnoremap <leader>r

\ :exec '!bash' shellescape(@%, 1)<cr>

autocmd FileType swift nnoremap <leader>r

\ :exec '!swift' shellescape(@%, 1)<cr>

nnoremap <leader>R :!<Up><CR>

augroup END

After using a fairly large, mature language for a reasonable period of time, finding peculiarities in the language or its libraries is guaranteed to happen. However, given its history, I have to say C++ definitely allows for some of the strangest peculiarities in its syntax. Below I list three that are my favorite.

Ternaries Returning lvalues

You might be familiar with ternaries as condition ? do something : do something else, and they become quite useful in comparison to the standard if-else. However, if you've dealt with ternaries a lot, you might have noticed that ternaries also return lvalues/rvalues. Now, as the name suggests, you can assign to lvalues (lvalues are often referred to as locator values). So something like this is possible:

std::string x = "foo", y = "bar";

std::cout << "Before Ternary! ";

// prints x: foo, y: bar

std::cout << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

// Use the lvalue from ternary for assignment

(1 == 1 ? x : y) = "I changed";

(1 != 1 ? x : y) = "I also changed";

std::cout << "After Ternary! ";

// prints x: I changed, y: I also changed

std::cout << "x: " << x << ", y: " << y << "\n";

Although it makes sense, it’s really daunting; I can attest to never seeing it in the wild.

Commutative Bracket Operator

An interesting fact about the C++ bracket operator: it's simply pointer arithmetic. Writing array[42] is actually the same as writing *(array + 42), and thinking in terms of x86/64 assembly, this makes sense! It's simply an indexed addressing mode, a base (the beginning location of array) followed by an offset (42). If this doesn't make sense, that's okay. We'll discuss the implications without any need for assembly programming.

So we can do something like *(array + 42), which is interesting, but we can do better. We know addition to be commutative, so wouldn't saying *(42 + array) be the same? Indeed it is, and by transitivity, array[42] is exactly the same as 42[array]. The following is a more concrete example.

std::string array[50];

42[array] = "answer";

// prints 42 is the answer

std::cout << "42 is the " << array[42] << ".";

Zero Width Space Identifiers

This one has the least to say, and could cause the most damage. The C++ standard allows for hidden white space in identifiers (i.e. variable names, method/property names, class names, etc.). So this makes the following possible.

int number = 1;

int number = 2;

int number = 3;

std::cout << number << std::endl; // prints 1

std::cout << number << std::endl; // prints 2

std::cout << number << std::endl; // prints 3

Using \u as a proxy for a hidden whitespace character, the above code can be rewritten as:

int n\uumber = 1;

int nu\umber = 2;

int num\uber = 3;

std::cout << n\uumber << std::endl; // prints 1

std::cout << nu\umber << std::endl; // prints 2

std::cout << num\uber << std::endl; // prints 3

So if you’re feeling like watching the world burn, this would be the way to go.

One of the most frustrating things to deal with is the trailing space. Trailing spaces are such a pain because

- They can screw up string literals

- They can break expectations in a text editor (i.e. jumping to a new line or the end of the line)

- They can actually break programming languages

- They are just unflattering

However, in Vim, it takes one autocmd to alleviate this.

augroup spaces

autocmd!

autocmd BufWritePre \* %s/s+$//e

augroup END

On every buffer save substitute spaces at the end of the line with nothing. Easy!