Code

Since reading about its faults in The Not So Short Introduction to LaTeX (highly recommended read), I've avidly stayed away from eqnarray. However, I don't think the book conveys the ideas as well as it should. Its suggestion was IEEEeqnarray, as opposed to the classically recommended align. This article from the TeX Users Group conveys them more eloquently and provides better alternatives.

The most frustrating thing about compiling LaTeX in a terminal is the wall of text that gets written to stdout. An easy solution would be piping to /dev/null—except then you wouldn't be able to get error messages (even if you only pipe stdout to /dev/null and keep stderr). So, I made a solution that handles compiling by piping error messages to less. The syntax latexerr FILENAME will compile the file. Passing --clean will delete temporary LaTeX files.

#!/bin/bash

# USAGE: ./script FILE --clean --glossary

extensions_to_delete=(\

gz fls fdb_latexmk blg bbl log\

aux out nav toc snm glg glo xdy

)

compile_and_open() {

argument="$1"

auxname="${argument%.tex}.aux"

errors=$(pdflatex -shell-escape \

-interaction=nonstopmode \

-file-line-error "$argument" | \

grep ".*:[0-9]*:.*")

if [[ -n $errors ]]; then

echo "$1 Errors Detected"

echo "$errors" | less

else

open_file $1

echo "$1 Compile Successful"

fi

}

open_file() {

filename=`echo "$1" | cut -d'.' -f1`

open "$filename.pdf"

echo "$filename Opened"

}

# http://tex.stackexchange.com/questions/6845/compile-latex-with-bibtex-and-glossaries

glossary() {

compile $1

makeglossaries $1

compile $1

compile $1

}

clean() {

for file in $(dirname $1)/*; do

filename=$(basename "$file")

extension="${filename##*.}"

filename="${filename%.*}"

for bad_extensions in "${extensions_to_delete[@]}" ; do

if [[ $bad_extensions = $extension ]]; then

rm $file

echo "$file Deleted"

fi

done

done

}

main() {

compile_and_open $1

if [ "$3" = "--glossary" ]; then

glossary $1

fi

if [ "$2" = "--clean" ]; then

clean $1

fi

}

main "$@"

The Monty Hall Problem

You've seen it in movies or read about it in books: the Monty Hall Problem. Here's how it works: you're on a game show. There are three doors—behind one is a prize, behind the other two is nothing but disappointment. You pick a door. The host, Monty Hall, opens one of the other doors and reveals there's no prize behind it. Keeping the other two doors closed, he asks if you'd like to switch your choice or stick with your original pick. What should you do? Ben Campbell has a solution.

You mean to tell me that switching mid-game—an offer from the man who set up all the doors and prizes—gives me better odds of winning? How is this possible? Seems a bit counterintuitive. Seems almost wrong. Fortunately, we can test this with a simple program.

import Darwin // for arc4random_uniform

func random(from from: Int, to: Int,

except: Array<Int>? = nil) -> Int {

// Produce bounds, +1 to make inclusive

let number = Int(arc4random_uniform(UInt32(to - from + 1))) + from

if except != nil && except?.indexOf(number) != nil {

// Recursively call until we find a valid number

return random(from: from, to: to, except: except)

}

return number

}

// Returns if you won when you stayed and switched, respectively

func montyHall(doors: Int) -> (Bool, Bool) {

let originalDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors)

let correctDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors)

// The door the host reveals

let revealedDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors,

except: [correctDoor, originalDoor])

// If you switched, this would be your new door

let switchedDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors,

except: [revealedDoor, originalDoor])

return (originalDoor == correctDoor, switchedDoor == correctDoor)

}

let testValues = [100, 1_000, 10_000, 100_000,

1_000_000, 10_000_000]

let actualNumberOfDoors = 3

for value in testValues {

var stayingCounter = 0, switchingCounter = 0

for _ in 0...value {

let (stayedWon, switchedWon) = montyHall(actualNumberOfDoors)

if stayedWon { stayingCounter += 1 }

if switchedWon { switchingCounter += 1 }

}

let output = "Test Case: \(value). " +

"Staying Won: \(stayingCounter), " +

"Switching Won: \(switchingCounter)"

print(output)

}

There's no tricks in the code. No gimmicks. So, the results?

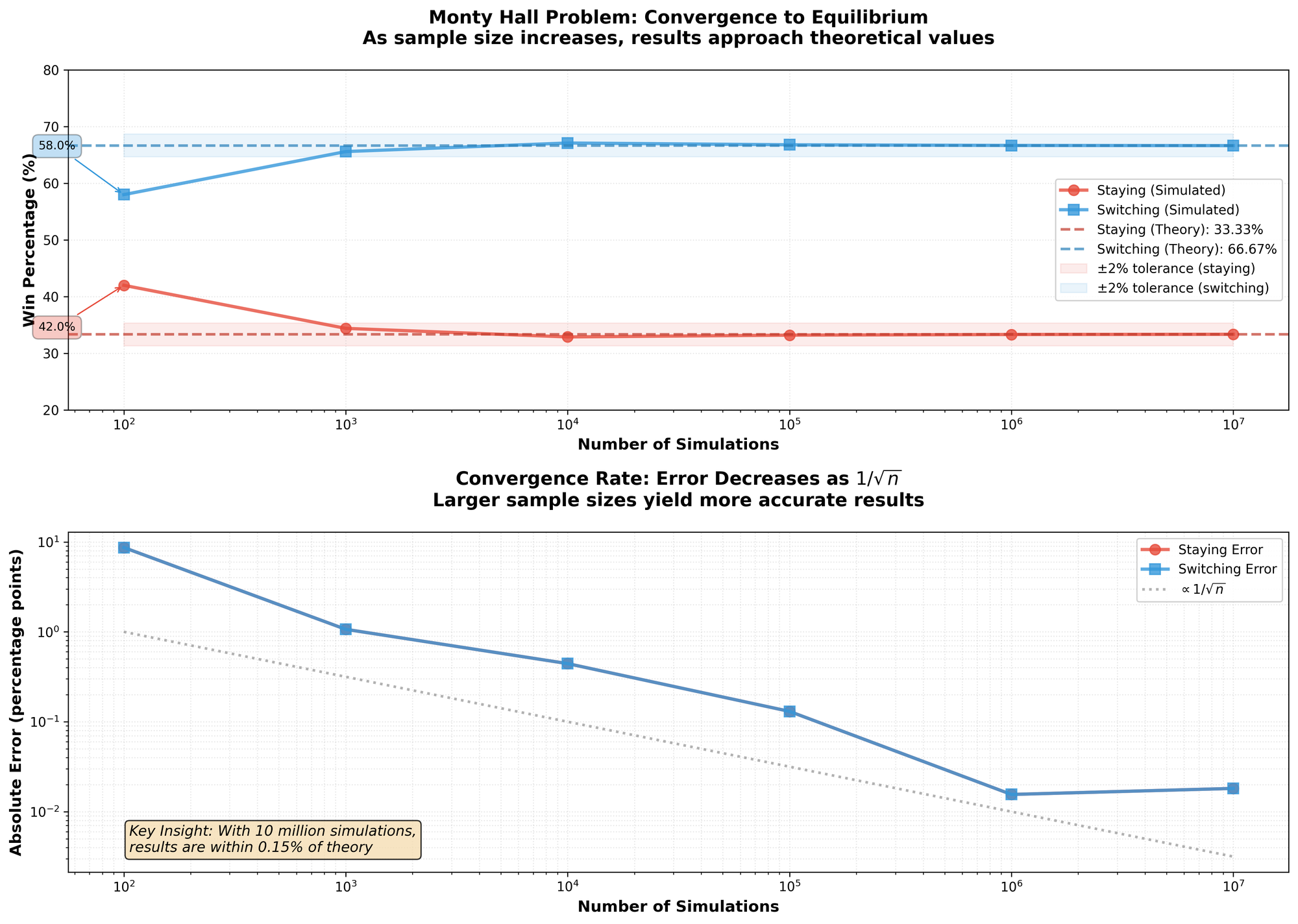

| Input | Staying Won | Switching Won |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 42 | 58 |

| 1000 | 344 | 656 |

| 10000 | 3289 | 6711 |

| 100000 | 33203 | 66797 |

| 1000000 | 333178 | 666822 |

| 10000000 | 3335146 | 6664854 |

It appears that Ben[1] was right. Taking the limit as the input gets higher, switching won roughly $66%$ of the time—compare that to the original $33%$ you got before you were given the option to switch doors. So, how is this possible? I'll explain.

For simplicity, suppose the prize is behind door A out of doors A, B, C. The argument can be made for any initial door, but A makes it easier. At this point, you have a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of picking the prize no matter what you pick. If you pick door A, the door which contains the prize, the host will definitely want you to change so he will offer you either door B or C. Now suppose you choose a door without the prize, either door B or C. The host has no choice but to eliminate the door without the prize. Meaning if you switch, you have the winning door.

So, why $66%$? Computationally, if you always switch and you picked the wrong door initially, your switch will win every time. There are two incorrect choices out of three, meaning $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time you will win.

You've just had your first lesson in conditional probability.

- 21 main character, played by Jim Sturgess ↩︎