Computer Science

Sorting Algorithms

sort

When I was a Teacher Assistant (TA) in Intro To Computer Science lab, fellow TA

Ian and I were showing off our programming prowess. I thought I had it in the bag: I had solved a competitive programming problem in compile-time (C++ templates are Turing-complete!) and a Space Invaders clone for a class.

But Ian was more clever than I, and showed me something that fundamentally changed how I saw a core-component of programming: a terminal-based (ncurses) sorting algorithm visualizers.

It was the first time I had ever seen these algorithms graphed like this — ever! And, yes, I blame my Algorithm instructor. I finally could see all the hypothetical sorting in a real-life application.

With the power of LLMs in hand, and a website as my canvas, I wanted to see if I could recreate this. Kudos to you, Ian.

Sorting algorithms form the backbone of computer science, serving as fundamental building blocks for countless applications from database management to search engines. This comprehensive guide examines the 25 most important sorting algorithms, organized by type, with detailed analysis of their performance, implementation, and practical applications.

1. Basic Comparison-Based Algorithms

These fundamental algorithms serve as the foundation for understanding sorting concepts, though they generally have O(n²) time complexity.

1.1 Bubble Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) / Ω(n) - when array is already sorted

- Average Case: O(n²) / Θ(n²)

- Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Stable, In-place, Adaptive

def bubble_sort(arr):

"""

Bubble Sort with optimization

Time: O(n²) average/worst, O(n) best

Space: O(1)

"""

n = len(arr)

for i in range(n):

swapped = False

# Last i elements are already sorted

for j in range(0, n - i - 1):

if arr[j] > arr[j + 1]:

arr[j], arr[j + 1] = arr[j + 1], arr[j]

swapped = True

# If no swapping occurred, array is sorted

if not swapped:

break

return arr

When to Use:

- Small datasets (< 50 elements)

- Educational purposes - excellent for teaching

- Nearly sorted data

- Memory-constrained environments

Step-by-Step Example:

Array: [64, 34, 25, 12, 22, 11, 90]

Pass 1: [34, 25, 12, 22, 11, 64, 90] - Largest element "bubbles" to end

Pass 2: [25, 12, 22, 11, 34, 64, 90]

... continues until sorted

History: First described by Edward Harry Friend in 1956. The name "bubble sort" was coined by Kenneth E. Iverson due to how smaller elements "bubble" to the top.

Notable Trivia: Donald Knuth famously stated "bubble sort seems to have nothing to recommend it, except a catchy name." Despite criticism, it remains the most taught sorting algorithm due to its simplicity.

1.2 Selection Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best/Average/Worst Case: O(n²) - always makes same comparisons

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place, Not adaptive

def selection_sort(arr):

"""

Selection Sort implementation

Time: O(n²) for all cases

Space: O(1)

"""

n = len(arr)

for i in range(n):

# Find minimum element in remaining unsorted array

min_idx = i

for j in range(i + 1, n):

if arr[j] < arr[min_idx]:

min_idx = j

# Swap the found minimum element

arr[i], arr[min_idx] = arr[min_idx], arr[i]

return arr

When to Use:

- When memory write operations are expensive (e.g., flash memory)

- Small datasets where simplicity matters

- When the number of swaps needs to be minimized

Key Advantage: Performs only O(n) swaps compared to O(n²) for bubble sort.

History: Has ancient origins in manual sorting processes. Formalized in the 1950s as one of the fundamental sorting methods.

1.3 Insertion Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) - already sorted

- Average/Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Stable, In-place, Adaptive, Online

def insertion_sort(arr):

"""

Insertion Sort implementation

Time: O(n²) average/worst, O(n) best

Space: O(1)

"""

for i in range(1, len(arr)):

key = arr[i]

j = i - 1

while j >= 0 and arr[j] > key:

arr[j + 1] = arr[j]

j -= 1

arr[j + 1] = key

return arr

When to Use:

- Small datasets (typically < 50 elements)

- Nearly sorted data - performs in O(n) time

- Online algorithms - when data arrives sequentially

- As a subroutine in quicksort and mergesort for small subarrays

Notable Use: Used in Timsort (Python's built-in sort) for small runs. Often faster than O(n log n) algorithms for arrays with fewer than 10-20 elements.

1.4 Shell Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n log n)

- Average Case: O(n^1.25) to O(n^1.5) depending on gap sequence

- Worst Case: O(n²) for Shell's original sequence

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place, Adaptive

def shell_sort(arr):

"""

Shell Sort using Shell's original sequence

Time: O(n²) worst case, O(n log n) average

Space: O(1)

"""

n = len(arr)

gap = n // 2

while gap > 0:

# Perform gapped insertion sort

for i in range(gap, n):

temp = arr[i]

j = i

while j >= gap and arr[j - gap] > temp:

arr[j] = arr[j - gap]

j -= gap

arr[j] = temp

gap //= 2

return arr

When to Use:

- Medium-sized datasets (100-5000 elements)

- When recursion should be avoided

- Embedded systems - simple and efficient

History: Invented by Donald L. Shell in 1959, it was one of the first algorithms to break the O(n²) barrier.

1.5 Cocktail Shaker Sort (Bidirectional Bubble Sort)

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n)

- Average/Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Stable, In-place, Adaptive, Bidirectional

def cocktail_shaker_sort(arr):

"""

Cocktail Shaker Sort (Bidirectional Bubble Sort)

Time: O(n²) average/worst, O(n) best

Space: O(1)

"""

n = len(arr)

start = 0

end = n - 1

while start < end:

swapped = False

# Forward pass

for i in range(start, end):

if arr[i] > arr[i + 1]:

arr[i], arr[i + 1] = arr[i + 1], arr[i]

swapped = True

if not swapped:

break

end -= 1

swapped = False

# Backward pass

for i in range(end, start, -1):

if arr[i] < arr[i - 1]:

arr[i], arr[i - 1] = arr[i - 1], arr[i]

swapped = True

if not swapped:

break

start += 1

return arr

Advantage: Better than bubble sort at moving small elements (turtles) to the beginning.

2. Efficient Comparison-Based Algorithms

These algorithms achieve O(n log n) average performance and form the backbone of many practical sorting implementations.

2.1 Quick Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best/Average Case: O(n log n)

- Worst Case: O(n²) - when pivot is always minimum/maximum

- Space: O(log n) - recursion stack

Properties: Unstable, In-place, Not adaptive

def quicksort(arr, low=0, high=None):

"""

Quicksort with Hoare partition scheme

Time: O(n log n) average, O(n²) worst

Space: O(log n)

"""

if high is None:

high = len(arr) - 1

if low < high:

pivot_idx = partition(arr, low, high)

quicksort(arr, low, pivot_idx)

quicksort(arr, pivot_idx + 1, high)

return arr

def partition(arr, low, high):

"""Hoare partition scheme"""

pivot = arr[low]

i = low - 1

j = high + 1

while True:

i += 1

while arr[i] < pivot:

i += 1

j -= 1

while arr[j] > pivot:

j -= 1

if i >= j:

return j

arr[i], arr[j] = arr[j], arr[i]

Why It's Preferred Despite O(n²) Worst Case:

- Excellent average-case performance with good constant factors

- Cache-friendly sequential access patterns

- In-place sorting

- Modern implementations use introsort to guarantee O(n log n)

History: Invented by Tony Hoare in 1959 while working on machine translation at Moscow State University.

2.2 Merge Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(n log n) - guaranteed performance

- Space: O(n) - requires additional space for merging

Properties: Stable, Not in-place, Not adaptive

def merge_sort(arr):

"""

Merge Sort implementation

Time: O(n log n) guaranteed

Space: O(n)

"""

if len(arr) <= 1:

return arr

mid = len(arr) // 2

left = merge_sort(arr[:mid])

right = merge_sort(arr[mid:])

return merge(left, right)

def merge(left, right):

"""Merge two sorted arrays"""

result = []

i = j = 0

while i < len(left) and j < len(right):

if left[i] <= right[j]:

result.append(left[i])

i += 1

else:

result.append(right[j])

j += 1

result.extend(left[i:])

result.extend(right[j:])

return result

When to Use:

- When stability is required

- External sorting (large datasets that don't fit in memory)

- Linked lists (efficient with O(1) extra space)

- Parallel processing

History: Invented by John von Neumann in 1945, with detailed analysis published in 1948.

2.3 Heap Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(n log n) - guaranteed performance

- Space: O(1) - true in-place sorting

Properties: Unstable, In-place, Not adaptive

def heap_sort(arr):

"""

Heap Sort implementation

Time: O(n log n) guaranteed

Space: O(1)

"""

n = len(arr)

# Build max heap

for i in range(n // 2 - 1, -1, -1):

heapify(arr, n, i)

# Extract elements from heap

for i in range(n - 1, 0, -1):

arr[0], arr[i] = arr[i], arr[0]

heapify(arr, i, 0)

return arr

def heapify(arr, n, i):

"""Maintain heap property"""

largest = i

left = 2 * i + 1

right = 2 * i + 2

if left < n and arr[left] > arr[largest]:

largest = left

if right < n and arr[right] > arr[largest]:

largest = right

if largest != i:

arr[i], arr[largest] = arr[largest], arr[i]

heapify(arr, n, largest)

When to Use:

- Memory-constrained environments

- Real-time systems (guaranteed performance)

- Systems concerned with malicious input

History: Invented by J. W. J. Williams in 1964, with in-place version by Robert Floyd.

2.4 Binary Tree Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best/Average Case: O(n log n) - with balanced tree

- Worst Case: O(n²) - with unbalanced tree

- Space: O(n) - for tree structure

Properties: Can be stable, Not in-place

When to Use:

- Educational purposes

- When tree structure is needed for other operations

- Online sorting

Note: Self-balancing trees (AVL, Red-Black) guarantee O(n log n) performance.

2.5 Smooth Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) - for sorted data

- Average/Worst Case: O(n log n)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place, Adaptive

History: Invented by Edsger W. Dijkstra in 1981 as an improvement over heapsort for partially sorted data.

Notable Use: Used in musl C library's qsort() implementation.

3. Non-Comparison Based Algorithms

These algorithms achieve linear O(n) time complexity by exploiting specific properties of the data rather than comparing elements.

3.1 Counting Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(n + k) where k is the range of values

- Space: O(n + k)

Properties: Stable, Not in-place

def counting_sort(arr):

"""

Counting Sort for non-negative integers

Time: O(n + k)

Space: O(n + k)

"""

if not arr:

return arr

max_val = max(arr)

count = [0] * (max_val + 1)

# Count occurrences

for num in arr:

count[num] += 1

# Calculate cumulative count

for i in range(1, len(count)):

count[i] += count[i - 1]

# Build output array

output = [0] * len(arr)

for i in range(len(arr) - 1, -1, -1):

output[count[arr[i]] - 1] = arr[i]

count[arr[i]] -= 1

return output

When to Use:

- Sorting integers in a small range

- As a subroutine in radix sort

- When k is O(n) or smaller

History: Invented by Harold H. Seward in 1954 at MIT.

3.2 Radix Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(d × (n + k)) where d is number of digits

- Space: O(n + k)

Properties:

- LSD (Least Significant Digit): Stable

- MSD (Most Significant Digit): Can be stable

def radix_sort_lsd(arr):

"""

LSD Radix Sort implementation

Time: O(d × (n + k))

Space: O(n + k)

"""

if not arr:

return arr

max_val = max(arr)

exp = 1

while max_val // exp > 0:

counting_sort_for_radix(arr, exp)

exp *= 10

return arr

def counting_sort_for_radix(arr, exp):

n = len(arr)

output = [0] * n

count = [0] * 10

for i in range(n):

index = arr[i] // exp

count[index % 10] += 1

for i in range(1, 10):

count[i] += count[i - 1]

i = n - 1

while i >= 0:

index = arr[i] // exp

output[count[index % 10] - 1] = arr[i]

count[index % 10] -= 1

i -= 1

for i in range(n):

arr[i] = output[i]

When to Use:

- Sorting integers with many digits

- String sorting (MSD variant)

- When d is small compared to log n

History: Dates back to 1887 with Herman Hollerith's tabulating machines.

3.3 Bucket Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best/Average Case: O(n + k) for uniform distribution

- Worst Case: O(n²) when all elements fall into one bucket

- Space: O(n + k)

Properties: Stable (if sub-sorting is stable), Not in-place

def bucket_sort(arr):

"""

Bucket Sort for floating-point number

Time: O(n + k) average

Space: O(n + k)

"""

if not arr:

return arr

min_val, max_val = min(arr), max(arr)

bucket_count = len(arr)

buckets = [[] for _ in range(bucket_count)]

# Distribute elements into buckets

for num in arr:

if max_val == min_val:

index = 0

else:

index = int((num - min_val) / (max_val - min_val) * (bucket_count - 1))

buckets[index].append(num)

# Sort individual buckets

result = []

for bucket in buckets:

if bucket:

bucket.sort() # Can use insertion sort

result.extend(bucket)

return result

When to Use:

- Uniformly distributed floating-point numbers

- Large datasets with known range

- When memory is not a constraint

3.4 Pigeonhole Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(n + range) where range = max - min + 1

- Space: O(range)

Properties: Stable, Not in-place

When to Use:

- Small range of integer values

- When range is comparable to n

- Simple counting applications

History: Based on the pigeonhole principle, formally described by A.J. Lotka (1926).

3.5 Flash Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best/Average Case: O(n) for uniform distribution

- Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(m) where m is number of classes

Properties: Unstable, In-place (major advantage)

When to Use:

- Large uniformly distributed datasets

- When memory is limited

- When O(n) average performance is critical

History: Invented by Karl-Dietrich Neubert in 1998 as an efficient in-place implementation of bucket sort.

4. Modern Hybrid Algorithms

These algorithms represent the state-of-the-art in practical sorting, combining multiple techniques for superior performance.

4.1 Timsort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) - already sorted

- Average/Worst Case: O(n log n)

- Space: O(n)

Properties: Stable, Not in-place

Key Innovations:

- Run Detection: Identifies naturally occurring sorted subsequences

- Minimum Run Size: Calculates optimal minrun (32-64 elements)

- Galloping Mode: Switches to exponential search when one run consistently "wins"

Where It's Used:

- Python's default sort since version 2.3

- Java for sorting objects (Java 7+)

- Android, V8, Swift, Rust

History: Created in 2002 by Tim Peters for Python. A critical bug was discovered and fixed in 2015 through formal verification.

4.2 Introsort (Introspective Sort)

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(n log n) - guaranteed by heapsort fallback

- Space: O(log n)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Techniques Combined:

- Quicksort for main sorting

- Heapsort when recursion depth exceeds 2×log₂(n)

- Insertion sort for small subarrays (< 16 elements)

Where It's Used:

- C++ STL's std::sort() in GCC and LLVM

- Microsoft .NET Framework 4.5+

History: Created by David Musser in 1997 to provide guaranteed O(n log n) performance while maintaining quicksort's average-case speed.

4.3 Block Sort (WikiSort)

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n)

- Average/Worst Case: O(n log n)

- Space: O(1) - constant space!

Properties: Stable, In-place

Key Innovation: Achieves stable merge sort performance with O(1) space by using internal buffering.

When to Use: When O(1) space complexity and stability are both required.

4.4 Pattern-defeating Quicksort (pdqsort)

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) for specific patterns

- Average/Worst Case: O(n log n)

- Space: O(log n)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Key Innovations:

- Pattern detection and optimization

- Branchless partitioning

- Adaptive strategy based on input characteristics

Where It's Used:

- Rust's default unstable sort

- C++ Boost libraries

History: Created by Orson Peters in 2016 to improve upon introsort with better pattern handling.

4.5 Dual-Pivot Quicksort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) when all elements equal

- Average Case: O(n log n) - 5% fewer comparisons than single-pivot

- Worst Case: O(n²) - still possible but less likely

- Space: O(log n)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Key Innovation: Uses two pivots to partition array into three parts, reducing comparisons.

Where It's Used: Java's default algorithm for primitive arrays since Java 7.

History: Created by Vladimir Yaroslavskiy in 2009, adopted by Java in 2011.

5. Specialized and Educational Algorithms

These algorithms serve specific purposes or demonstrate important concepts in computer science education.

5.1 Comb Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n log n)

- Average Case: O(n²/2^p) where p is number of increments

- Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Key Feature: Improves upon bubble sort using variable gap with shrink factor of 1.3.

History: Developed by Włodzimierz Dobosiewicz in 1980 to address bubble sort's inefficiency.

5.2 Gnome Sort (Stupid Sort)

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n)

- Average/Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Stable, In-place, Adaptive

Unique Feature: Uses only a single while loop - inspired by garden gnomes sorting flower pots.

5.3 Cycle Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- All Cases: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Key Feature: Minimizes memory writes - each element is written at most once to its correct position.

When to Use: When memory write operations are expensive (EEPROM, Flash memory).

5.4 Pancake Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n)

- Average/Worst Case: O(n²)

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Unique Constraint: Only allowed operation is "flip" (reverse prefix).

Historical Note: Bill Gates' only published academic paper was on this problem (1979), providing a (5n+5)/3 upper bound algorithm.

5.5 Bogo Sort

Complexity Analysis:

- Best Case: O(n) - already sorted

- Average Case: O(n·n!) - expected permutations

- Worst Case: O(∞) - theoretically unbounded

- Space: O(1)

Properties: Unstable, In-place

Educational Value:

- Demonstrates worst-case analysis

- Teaches randomized algorithms

- Shows importance of algorithm selection

import random

def bogo_sort(arr):

"""The worst sorting algorithm ever conceived"""

def is_sorted(arr):

return all(arr[i] <= arr[i+1] for i in range(len(arr)-1))

while not is_sorted(arr):

random.shuffle(arr)

return arr

Trivia: "Quantum Bogo Sort" hypothetically destroys universes where array isn't sorted, leaving only sorted universes.

Summary and Recommendations

Performance Comparison Table

| Algorithm | Best Case | Average Case | Worst Case | Space | Stable | In-Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble Sort | O(n) | O(n²) | O(n²) | O(1) | Yes | Yes |

| Selection Sort | O(n²) | O(n²) | O(n²) | O(1) | No | Yes |

| Insertion Sort | O(n) | O(n²) | O(n²) | O(1) | Yes | Yes |

| Quick Sort | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n²) | O(log n) | No | Yes |

| Merge Sort | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n) | Yes | No |

| Heap Sort | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(1) | No | Yes |

| Counting Sort | O(n+k) | O(n+k) | O(n+k) | O(n+k) | Yes | No |

| Radix Sort | O(d(n+k)) | O(d(n+k)) | O(d(n+k)) | O(n+k) | Yes | No |

| Timsort | O(n) | O(n log n) | O(n log n) | O(n) | Yes | No |

When to Use Which Algorithm

For Small Datasets (< 50 elements):

- Insertion Sort - simple and efficient

- Selection Sort - when minimizing swaps matters

For General Purpose:

- Timsort (Python) or Introsort (C++) - best overall performance

- Quick Sort with good pivot selection - excellent average case

For Guaranteed Performance:

- Merge Sort - stable and predictable

- Heap Sort - when O(1) space is required

For Special Data Types:

- Counting Sort - small integer ranges

- Radix Sort - large integers or strings

- Bucket Sort - uniformly distributed floats

For Educational Purposes:

- Start with Bubble Sort for simplicity

- Progress to Quick Sort and Merge Sort

- Use Bogo Sort to demonstrate algorithm analysis

Key Takeaways

- No single best algorithm - choice depends on data characteristics, constraints, and requirements

- Modern algorithms are hybrids - combining techniques yields superior performance

- Stability matters for sorting complex objects where maintaining relative order is important

- Space-time tradeoffs are crucial - some algorithms trade memory for speed

- Real-world performance often differs from theoretical complexity due to cache effects, data patterns, and implementation details

Understanding these 25 algorithms provides a comprehensive foundation for tackling sorting problems in any context, from embedded systems to large-scale data processing.

Evolutionary Algorithms Endgame Dynamics

Adaptive Restarts and Termination Conditions

Update: Previously, a system was introduced for detecting if an individual was stuck at a local optimum. After extensive testing, this system was shown to be fragile. This post has been updated to showcase a more robust system.

Previously our Evolutionary Algorithms had it pretty easy: there would be either one local optimum (like our Secret Message problem instance) or multiple valid local optima (like the 3-SAT problem instance). In the real world, we might not be so lucky.

Often, an Evolutionary Algorithm might encounter a local optimum within the search space, and it will not be so easy to escape — offspring generated will be in close proximity of the optimum, and the mutation will not be enough to start exploring other parts of the search space.

To add to the frustration, there might not enough time or patience to wait for the Evolutionary Algorithm to finish. We might have different criteria we are looking for, outside of just a fitness target.

We are going to tackle both of these issues.

Applying Termination Conditions

First, we will examine what criteria we want met before our Evolutionary Algorithm terminates. In general, there are six that are universal:

- Date and Time. After a specified date and time, terminate.

- Fitness Target. This is what we had before; terminate when any individual attains a certain fitness.

- Number of Fitness Evaluations. Every generation, every individual's fitness is evaluated (in our case, every generation $\mu + \lambda$ fitnesses are evaluated). Terminate after a specified number of fitness evaluations.

- Number of Generations. Just like the number of fitness evaluations, terminate after a specified generations.

- No Change In Average Fitness. This is a bit tricky. After specify $N$ generations, we check every $N$ generations back to determine if the average fitness of a population has improved. We have to be careful in our programming; by preserving diversity, we almost always lose fitness.

- No Change In Best Fitness. Just like No Change In Average Fitness, but instead of taking the average fitness, we take the best.

Later, we will see how Conditions 5 & 6 will come in handy to determining if we are stuck in a local optimum.

To make sure we are always given valid termination conditions, we will have a super class that all termination conditions will inherit from. From there, we will have a separate condition for each of the listed conditions above.

class _TerminationCondition:

pass

class FitnessTarget(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after an individual reaches a particular fitness."""

class DateTarget(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after a particular date and time."""

class NoChangeInAverageFitness(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after there has been no change in the average

fitness for a period of time."""

class NoChangeInBestFitness(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after there has been no change in the best fitness

for a period of time."""

class NumberOfFitnessEvaluations(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after a particular number of fitness evaluations."""

class NumberOfGenerations(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after a particular number of generations."""

Now, we need something that will keep track of all these conditions, and tells us when we should terminate. And here's where we need to be careful.

First, we need to know when to terminate. We want to mix and match different conditions, depending on the use case. This begs the questions:

Should the Evolutionary Algorithm terminate when one condition has been met, or all of them?

Generally, it makes more sense to terminate when any of the conditions have been met, as opposed to all of them. Suppose the two termination conditions are date and target fitness. It does not make sense to keep going after the target fitness is reached, and (if in a time crunch) it does not make sense to keep going after a specified date.

Second, how should we define no change in average/best fitness? These values can be quite sinusoidal, so we want to be more conservative in our definition. One plausible solution is to take the average of the first quartile (the first 25% to ever enter the queue), and see if the there is a single individual with a better fitness in the second, third, or fourth quartile (the last 75% percent to enter the queue). This way, even if there were very dominant individuals in the beginning, a single, more dominant individual will continue the Evolutionary Algorithm.

From this, we have everything we might need to keep track of our terminating conditions.

class TerminationManager:

def __init__(self, termination_conditions, fitness_selector):

assert isinstance(termination_conditions, list)

assert all(issubclass(type(condition), _TerminationCondition)

for condition in termination_conditions), \

"Termination condition is not valid"

self.termination_conditions = termination_conditions

self.__fitness_selector = fitness_selector

self.__best_fitnesses = []

self.__average_fitnesses = []

self.__number_of_fitness_evaluations = 0

self.__number_of_generations = 0

def should_terminate(self):

for condition in self.termination_conditions:

if (isinstance(condition, FitnessTarget) and

self.__fitness_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, DateTarget) and

self.__date_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NoChangeInAverageFitness) and

self.__average_fitness_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NoChangeInBestFitness) and

self.__best_fitness_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NumberOfFitnessEvaluations) and

self.__fitness_evaluations_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NumberOfGenerations) and

self.__generations_should_terminate()):

return True

return False

def reset(self):

"""Reset the best fitnesses, average fitnesses, number of

generations, and number of fitness evaluations."""

self.__best_fitnesses = []

self.__average_fitnesses = []

self.__number_of_fitness_evaluations = 0

self.__number_of_generations = 0

def __fitness_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the max fitness."""

def __date_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the date."""

def __average_fitness_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the average fitness

for the last N generations."""

def __best_fitness_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the average fitness

for the last N generations."""

def __fitness_evaluations_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the number of

fitness evaluations."""

def __generations_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the number of generations."""

And the changes to our Evolutionary Algorithm are minimal, too.

class EA:

...

def search(self, termination_conditions):

generation = 1

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

fitness_getter = lambda: [individual.fitness

for individual

in self.population.individuals]

termination_manager = TerminationManager(termination_conditions,

fitness_getter)

while not termination_manager.should_terminate():

offspring = Population.generate_offspring(self.population)

self.population.individuals += offspring.individuals

self.population = Population.survival_selection(

self.population)

print("Generation #{}: {}".format(

generation, self.population.fittest.fitness))

generation += 1

print("Result: {}".format(self.population.fittest.genotype))

return self.population.fittest

However, we can still do better.

Generations Into Epochs

Before, the Evolutionary Algorithm framework we put in place was strictly a generational model. One generation lead to the next, and there were no discontinuities. Now, let's make our generational model into an epochal one.

We define an epoch as anytime our Evolutionary Algorithm encounters a local optimum. Once the end of an epoch is reached, the EA is reset, and the previous epoch is saved. Upon approaching the end of the next epoch, reintroduce the last epoch into the population; by this, more of the search space is covered.

How can we determine if we are at a local optimum?

We can't.

That does not mean we cannot have a heuristic for it. When there is little to no change in average/best fitness for a prolonged period of time, that typically means a local optimum has been reached. How long is a prolonged period of time? That's undetermined; it is another parameter we have to account for.

Note, if the Evolutionary Algorithm keeps producing more fit individuals, but the average fitness remains the same, the algorithm will terminate. Likewise, if the best fitness remains the same, but the average fitness closely approaches the best, the EA will terminate. Therefore, we should determine if the best fitness and the average fitness has not changed; only then should we start a new epoch.

Luckily, we already have something that will manage the average/best fitness for us.

class EA:

...

def search(self, termination_conditions):

epochs, generation, total_generations = 1, 1, 1

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

previous_epoch = []

fitness_getter = lambda: [individual.fitness

for individual

in self.population.individuals]

termination_manager = TerminationManager(termination_conditions,

fitness_getter)

epoch_manager_best_fitness = TerminationManager(

[NoChangeInBestFitness(250)], fitness_getter)

epoch_manager_average_fitness = TerminationManager(

[NoChangeInAverageFitness(250)], fitness_getter)

while not termination_manager.should_terminate():

if (epoch_manager_best_fitness.should_terminate() and

epoch_manager_average_fitness.should_terminate()):

if len(previous_epoch) > 0:

epoch_manager_best_fitness.reset()

epoch_manager_average_fitness.reset()

self.population.individuals += previous_epoch

previous_epoch = []

else:

epoch_manager_best_fitness.reset()

epoch_manager_average_fitness.reset()

previous_epoch = self.population.individuals

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

generation = 0

epochs += 1

self.population = Population.survival_selection(self.population)

offspring = Population.generate_offspring(self.population)

self.population.individuals += offspring.individuals

self.__log(total_generations, epochs, generation)

total_generations += 1

generation += 1

print("Result: {}".format(self.population.fittest.genotype))

return self.population.fittest

def __log(self, total_generations, epochs, generation):

"""Log the process of the Evolutionary Algorithm."""

...

Although considerably more complicated, this new Evolutionary Algorithm framework allows us to explore much more of a search space (without getting stuck).

Let's put it to the test.

A New 3-SAT Problem

We're going to take on a substantially harder 3-SAT instance: 1,000 clauses, 250 variables. To make it worse, the number of valid solutions is also lower. We will also include the following terminating conditions:

- Time of eight hours.

- Fitness of all clauses satisfied (100).

- A million generations.

So, how does our Evolutionary Algorithm fare?

Not well. After twenty epochs, and thousands of generations — we do not find a solution. Fear not; in subsequent posts, we will work on optimizing our Genetic Algorithm to handle much larger cases, more effectively.

Update: Previously, a system was introduced for detecting if an individual was stuck at a local optimum. After extensive testing, this system was shown to be fragile. This post has been updated to showcase a more robust system.

Previously our Evolutionary Algorithms had it pretty easy: there would be either one local optimum (like our Secret Message problem instance) or multiple valid local optima (like the 3-SAT problem instance). In the real world, we might not be so lucky.

Often, an Evolutionary Algorithm might encounter a local optimum within the search space, and it will not be so easy to escape — offspring generated will be in close proximity of the optimum, and the mutation will not be enough to start exploring other parts of the search space.

To add to the frustration, there might not enough time or patience to wait for the Evolutionary Algorithm to finish. We might have different criteria we are looking for, outside of just a fitness target.

We are going to tackle both of these issues.

Applying Termination Conditions

First, we will examine what criteria we want met before our Evolutionary Algorithm terminates. In general, there are six that are universal:

- Date and Time. After a specified date and time, terminate.

- Fitness Target. This is what we had before; terminate when any individual attains a certain fitness.

- Number of Fitness Evaluations. Every generation, every individual's fitness is evaluated (in our case, every generation $\mu + \lambda$ fitnesses are evaluated). Terminate after a specified number of fitness evaluations.

- Number of Generations. Just like the number of fitness evaluations, terminate after a specified generations.

- No Change In Average Fitness. This is a bit tricky. After specify $N$ generations, we check every $N$ generations back to determine if the average fitness of a population has improved. We have to be careful in our programming; by preserving diversity, we almost always lose fitness.

- No Change In Best Fitness. Just like No Change In Average Fitness, but instead of taking the average fitness, we take the best.

Later, we will see how Conditions 5 & 6 will come in handy to determining if we are stuck in a local optimum.

To make sure we are always given valid termination conditions, we will have a super class that all termination conditions will inherit from. From there, we will have a separate condition for each of the listed conditions above.

class _TerminationCondition:

pass

class FitnessTarget(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after an individual reaches a particular fitness."""

class DateTarget(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after a particular date and time."""

class NoChangeInAverageFitness(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after there has been no change in the average

fitness for a period of time."""

class NoChangeInBestFitness(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after there has been no change in the best fitness

for a period of time."""

class NumberOfFitnessEvaluations(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after a particular number of fitness evaluations."""

class NumberOfGenerations(_TerminationCondition):

"""Terminate after a particular number of generations."""

Now, we need something that will keep track of all these conditions, and tells us when we should terminate. And here's where we need to be careful.

First, we need to know when to terminate. We want to mix and match different conditions, depending on the use case. This begs the questions:

Should the Evolutionary Algorithm terminate when one condition has been met, or all of them?

Generally, it makes more sense to terminate when any of the conditions have been met, as opposed to all of them. Suppose the two termination conditions are date and target fitness. It does not make sense to keep going after the target fitness is reached, and (if in a time crunch) it does not make sense to keep going after a specified date.

Second, how should we define no change in average/best fitness? These values can be quite sinusoidal, so we want to be more conservative in our definition. One plausible solution is to take the average of the first quartile (the first 25% to ever enter the queue), and see if the there is a single individual with a better fitness in the second, third, or fourth quartile (the last 75% percent to enter the queue). This way, even if there were very dominant individuals in the beginning, a single, more dominant individual will continue the Evolutionary Algorithm.

From this, we have everything we might need to keep track of our terminating conditions.

class TerminationManager:

def __init__(self, termination_conditions, fitness_selector):

assert isinstance(termination_conditions, list)

assert all(issubclass(type(condition), _TerminationCondition)

for condition in termination_conditions), \

"Termination condition is not valid"

self.termination_conditions = termination_conditions

self.__fitness_selector = fitness_selector

self.__best_fitnesses = []

self.__average_fitnesses = []

self.__number_of_fitness_evaluations = 0

self.__number_of_generations = 0

def should_terminate(self):

for condition in self.termination_conditions:

if (isinstance(condition, FitnessTarget) and

self.__fitness_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, DateTarget) and

self.__date_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NoChangeInAverageFitness) and

self.__average_fitness_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NoChangeInBestFitness) and

self.__best_fitness_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NumberOfFitnessEvaluations) and

self.__fitness_evaluations_should_terminate()):

return True

elif (isinstance(condition, NumberOfGenerations) and

self.__generations_should_terminate()):

return True

return False

def reset(self):

"""Reset the best fitnesses, average fitnesses, number of

generations, and number of fitness evaluations."""

self.__best_fitnesses = []

self.__average_fitnesses = []

self.__number_of_fitness_evaluations = 0

self.__number_of_generations = 0

def __fitness_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the max fitness."""

def __date_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the date."""

def __average_fitness_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the average fitness

for the last N generations."""

def __best_fitness_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the average fitness

for the last N generations."""

def __fitness_evaluations_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the number of

fitness evaluations."""

def __generations_should_terminate(self):

"""Determine if should terminate based on the number of generations."""

And the changes to our Evolutionary Algorithm are minimal, too.

class EA:

...

def search(self, termination_conditions):

generation = 1

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

fitness_getter = lambda: [individual.fitness

for individual

in self.population.individuals]

termination_manager = TerminationManager(termination_conditions,

fitness_getter)

while not termination_manager.should_terminate():

offspring = Population.generate_offspring(self.population)

self.population.individuals += offspring.individuals

self.population = Population.survival_selection(

self.population)

print("Generation #{}: {}".format(

generation, self.population.fittest.fitness))

generation += 1

print("Result: {}".format(self.population.fittest.genotype))

return self.population.fittest

However, we can still do better.

Generations Into Epochs

Before, the Evolutionary Algorithm framework we put in place was strictly a generational model. One generation lead to the next, and there were no discontinuities. Now, let's make our generational model into an epochal one.

We define an epoch as anytime our Evolutionary Algorithm encounters a local optimum. Once the end of an epoch is reached, the EA is reset, and the previous epoch is saved. Upon approaching the end of the next epoch, reintroduce the last epoch into the population; by this, more of the search space is covered.

How can we determine if we are at a local optimum?

We can't.

That does not mean we cannot have a heuristic for it. When there is little to no change in average/best fitness for a prolonged period of time, that typically means a local optimum has been reached. How long is a prolonged period of time? That's undetermined; it is another parameter we have to account for.

Note, if the Evolutionary Algorithm keeps producing more fit individuals, but the average fitness remains the same, the algorithm will terminate. Likewise, if the best fitness remains the same, but the average fitness closely approaches the best, the EA will terminate. Therefore, we should determine if the best fitness and the average fitness has not changed; only then should we start a new epoch.

Luckily, we already have something that will manage the average/best fitness for us.

class EA:

...

def search(self, termination_conditions):

epochs, generation, total_generations = 1, 1, 1

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

previous_epoch = []

fitness_getter = lambda: [individual.fitness

for individual

in self.population.individuals]

termination_manager = TerminationManager(termination_conditions,

fitness_getter)

epoch_manager_best_fitness = TerminationManager(

[NoChangeInBestFitness(250)], fitness_getter)

epoch_manager_average_fitness = TerminationManager(

[NoChangeInAverageFitness(250)], fitness_getter)

while not termination_manager.should_terminate():

if (epoch_manager_best_fitness.should_terminate() and

epoch_manager_average_fitness.should_terminate()):

if len(previous_epoch) > 0:

epoch_manager_best_fitness.reset()

epoch_manager_average_fitness.reset()

self.population.individuals += previous_epoch

previous_epoch = []

else:

epoch_manager_best_fitness.reset()

epoch_manager_average_fitness.reset()

previous_epoch = self.population.individuals

self.population = Population(self.μ, self.λ)

generation = 0

epochs += 1

self.population = Population.survival_selection(self.population)

offspring = Population.generate_offspring(self.population)

self.population.individuals += offspring.individuals

self.__log(total_generations, epochs, generation)

total_generations += 1

generation += 1

print("Result: {}".format(self.population.fittest.genotype))

return self.population.fittest

def __log(self, total_generations, epochs, generation):

"""Log the process of the Evolutionary Algorithm."""

...

Although considerably more complicated, this new Evolutionary Algorithm framework allows us to explore much more of a search space (without getting stuck).

Let's put it to the test.

A New 3-SAT Problem

We're going to take on a substantially harder 3-SAT instance: 1,000 clauses, 250 variables. To make it worse, the number of valid solutions is also lower. We will also include the following terminating conditions:

- Time of eight hours.

- Fitness of all clauses satisfied (100).

- A million generations.

So, how does our Evolutionary Algorithm fare?

Not well. After twenty epochs, and thousands of generations — we do not find a solution. Fear not; in subsequent posts, we will work on optimizing our Genetic Algorithm to handle much larger cases, more effectively.

Evolutionary Algorithms Recombination Operators

Permutation, Integer, and Real-Valued Crossover

We have been introduced to recombination operators before; however, that was merely an introduction. There are dozens of different Evolutionary Algorithm recombination operators for any established genotype; some are simple, some are complicated.

For a genotype representation that is a permutation (such as a vector[1], bit-string, or hash-map[2]), we have seen a possible recombination operator. Our 3-SAT solver uses a very popular recombination technique: uniform crossover.

Furthermore, we know a permutation is not the only, valid genotype for an individual: other possibilities can include an integer or a real-valued number.

Note, for simplicity, we will discuss recombination to form one offspring. This exact process can be applied to form a second child (generally with the parent's role reversed). Recombination can also be applied to more than two parents (depending on the operator). Again, for simplicity, we choose to omit it[3].

First, let us start with permutations.

Permutation Crossover

In regard to permutation crossover, there are three common operators:

- Uniform Crossover

- $N$ -Point Crossover

- Davis Crossover

Uniform crossover we have seen before. We consider individual elements in the permutation, and choose one with a random, equal probability. For large enough genotypes, the offspring genotype should consist of 50% of the genotype from parent one, and 50% of the genotype from parent two.

$N$-Point crossover considers segments of a genotype, as opposed to individual elements. This operator splits the genotype of Parent 1 and Parent 2 $N$ times (hence the name $N$-point), and creates a genotype by alternating segments from the two parents. For every $N$, there will be $N + 1$ segments. For 1-point crossover, the genotype should be split into two segments, and the offspring genotype should be composed of one segment from Parent 1, and one segment from Parent 2. For 2-point crossover, there will be three segments, and the offspring genotype will have two parts from Parent 1 and one part from Parent 2 (or two parts, Parent 1, one part, Parent 2).

Davis Crossover tries to preserve the ordering of the genotype in the offspring (as opposed to the previous methods, where ordering was not considered). The premise is a bit complicated, but bear with me. Pick two random indices ($k_1$ and $k_2$), and copy the genetic material of Parent 1 from $k_1$ to $k_2$ into the offspring at $k_1$ to $k_2$. Put Parent 1 to the side, his role is finished. Start copying the genotype of Parent 2 starting at $k_1$ to $k_2$ at the beginning of the offspring. When $k_2$ is reached in the parent, start copying the beginning of Parent 2 into the genotype, and when $k_1$ is reached in the parent, skip to $k_2$. When $k_1$ is reached in the offspring, skip to $k_2$, and start copying until the end. If this seems a complicated (it very much is), reference the accompanying figure.

Those are considered the three, most popular choices for permutations. Now, let us look at integer crossover.

Integer Crossover

Integer crossover is actually quite an interesting case; integers can be recombined as permutations or real-valued numbers.

An integer is already a permutation, just not at first glance: binary. The individual bits in a binary string are analogous to elements in a vector, and the whole collection is a vector. Now it is a valid permutation. We can apply uniform crossover, $N$-point crossover, or Davis Crossover, just as we have seen.

An integer is also already a real-valued number, so we can treat it as such. Let's take a look at how to recombine it.

Real-Valued Crossover

Real-Valued crossover is different than methods we have seen before. We could turn it into binary, but that would be a nightmare to deal with. However, we can exploit the arithmetic properties of real-valued numbers — with a weighted, arithmetic mean. For a child (of real value) $z$, we can generate it from Parent 1 $x$ and Parent 2 $y$ as such:

$$

z = \alpha \cdot x + (1 - \alpha) \cdot y

$$

Now, if we want to crossover a permutation of Parent 1 and Parent 2, we can do so for every element.

$$

z_i = \alpha \cdot x_i + (1 - \alpha) \cdot y_i

$$

This can be shown to have better performance than crossover methods discussed, but would entirely depend on use case.

Implementing Permutation Recombination

As always, we will now tackle implementing the permutation crossovers we've had before. None of them are incredibly complicated, except possibly $N$-point crossover.

class Individual

...

@staticmethod

def __uniform_crossover(parent_one, parent_two):

new_genotype = SAT(Individual.cnf_filename)

for variable in parent_one.genotype.variables:

gene = choice([parent_one.genotype[variable],

parent_two.genotype[variable]])

new_genotype[variable] = gene

individual = Individual()

individual.genotype = new_genotype

return individual

@staticmethod

def __n_point_crossover(parent_one, parent_two, n):

new_genotype = SAT(Individual.cnf_filename)

variables = sorted(parent_one.genotype.variables)

splits = [(i * len(variables) // (n + 1)) for i in range(1, n + 2)]

i = 0

for index, split in enumerate(splits):

for variable_index in range(i, split):

if index % 2 == 0:

gene = parent_one.genotype[variables[i]]

else:

gene = parent_two.genotype[variables[i]]

new_genotype[variables[i]] = gene

i += 1

individual = Individual()

individual.genotype = new_genotype

return individual

@staticmethod

def __davis_crossover(parent_one, parent_two):

new_genotype = SAT(Individual.cnf_filename)

variables = sorted(parent_one.genotype.variables)

split_one, split_two = sorted(sample(range(len(variables)), 2))

for variable in variables[:split_one]:

new_genotype[variable] = parent_two.genotype[variable]

for variable in variables[split_one:split_two]:

new_genotype[variable] = parent_one.genotype[variable]

for variable in variables[split_two:]:

new_genotype[variable] = parent_two.genotype[variable]

individual = Individual()

individual.genotype = new_genotype

return individual

Recombination In General

By no means is recombination easy. It took evolution hundreds of thousands of years to formulate ours. The particular permutation operator to use entirely dependent on the context of the problem; and most of the time, it is not obvious by any stretch. Sometimes, there might not even be an established crossover operator for a particular genotype.

Sometimes, you might have to get a little creative.

Search algorithms have a tendency to be complicated. Genetic algorithms have a lot of theory behind them. Adversarial algorithms[1] have to account for two, conflicting agents. Informed search relies heavily on heuristics. Well, there is one algorithm that is quite easy to grasp right off the bat.

Imagine you are at the bottom of a hill; you have no idea where to go. A decent place to start would be to go up the hill to survey the landscape. Then, restart to find a higher peak until you find the highest peak, right? Well, that is the entire algorithm.

Let's dig a bit deeper.

An Introduction

What is Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climbing, formally? It's nothing more than an agent searching a search space, trying to find a local optimum. It does so by starting out at a random Node, and trying to go uphill at all times.

The pseudocode is rather simple:

current ← Generate-Initial-Node()

while true

neighbors ← Generate-All-Neighbors(current)

successor ← Highest-Valued-Node(neighbors)

if Value-At-Node(successor) <= Value-At-Node(current):

return current

current ← successor

What is this Value-At-Node and $f$-value mentioned above? It's nothing more than a heuristic value that used as some measure of quality to a given node. Some examples of these are:

- Function Maximization: Use the value at the function $f(x, y, \ldots, z)$.

- Function Minimization: Same as before, but the reciprocal: $1 / f(x, y, \ldots, z)$.

- Path-Finding: Use the reciprocal of the Manhattan distance.

- Puzzle-Solving: Use some heuristic to determine how well/close the puzzle is solved.

The best part? If the problem instance can have a heuristic value associated with it, and be able to generate points within the search space, the problem is a candidate for Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climbing.

Implementing Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climbing

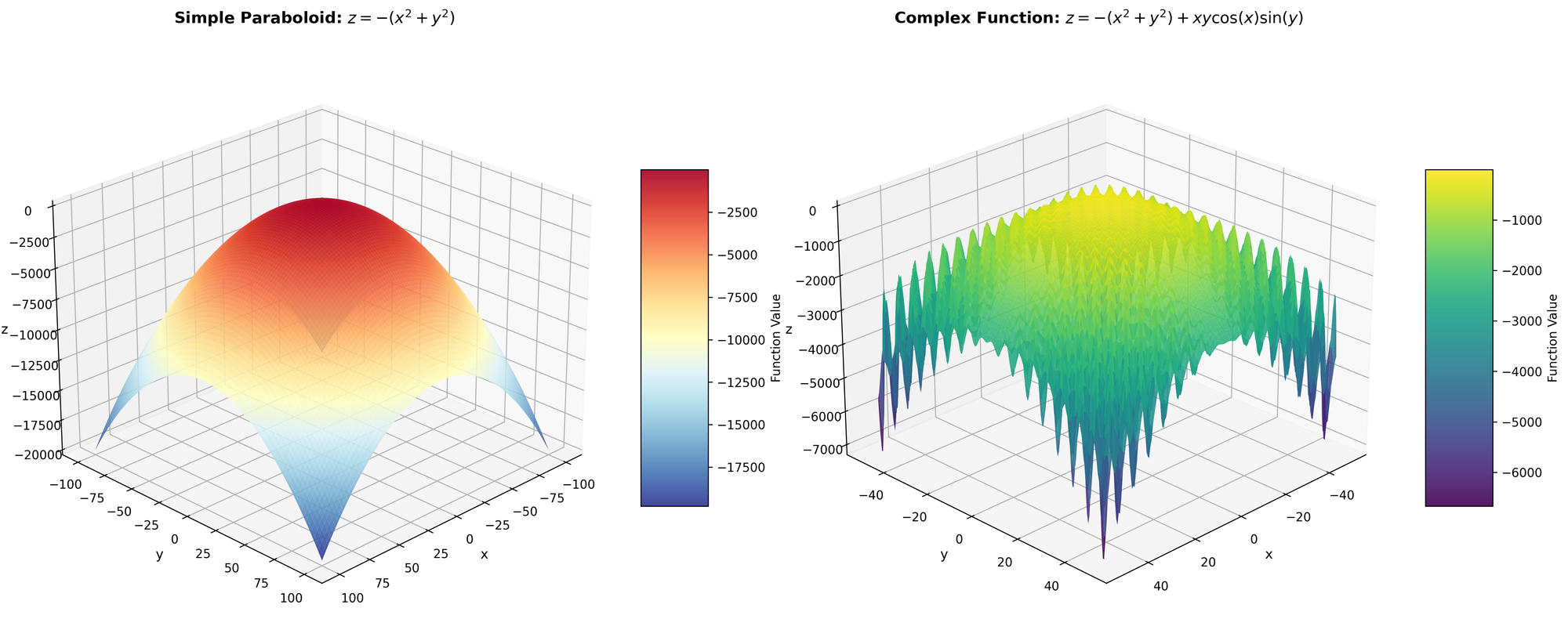

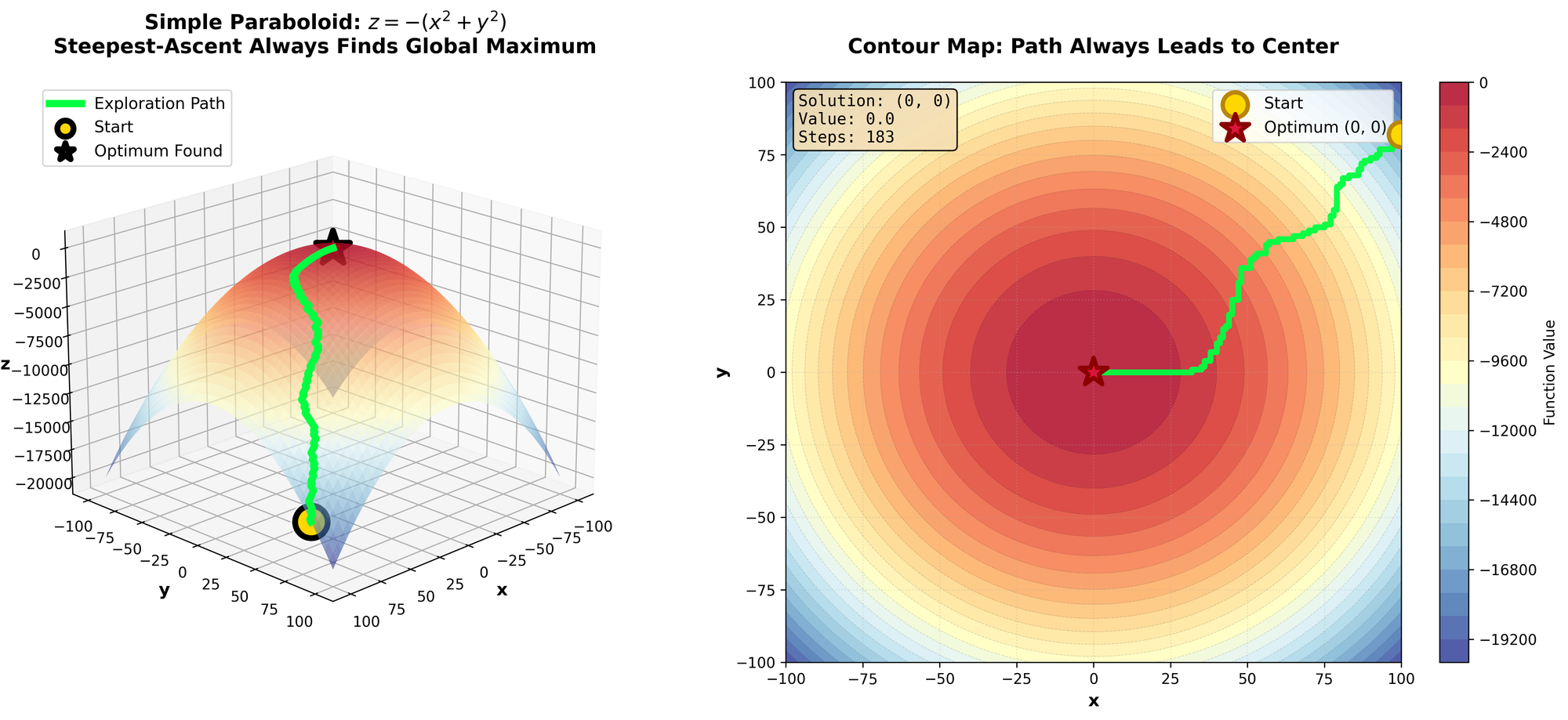

For this problem, we are going to solve an intuitive problem: function maximization. Given a function $z = f(x, y)$, for what values of $x, y$ will $z$ be the largest? To start, we are going to use a trivial function to maximize:

$$

z = -x^2 - y^2

$$

We see it is nothing more than a paraboloid. Furthermore, since it is infinite, we are going to restrict the domain to ${ x, y \in \mathbb{Z}^+ : -100 \leq x, y \leq 100 }$; therefore, we only have integer values between $(-100, 100)$.

So, let's begin.

The Representation

Because we will be searching throughout a search space, we will need some representation of a state. For our particular problem instance, it's very easy: the points $(x, y)$. Also, we will need to represent the $f$ value, so we create an auxiliary class as well.

class Node:

"""A node in a search space (similar to a point (x, y)."""

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

class Function:

"""A function and its respective bounds."""

def __init__(self, function, x_bounds, y_bounds):

...

def __call__(self, node):

...

@property

def x_bounds(self):

"""Get the x bounds of the function.

Returns:

tuple<int, int>: The x bounds of function in the format (min, max).

"""

...

@property

def y_bounds(self):

"""Get the y bounds of the function.

Returns:

tuple<int, int>: The y bounds of function in the format (min, max).

"""

...

That will be all that we need for our purposes.

Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climbing

As we saw before, there are only four moving pieces that our hill-climbing algorithm has: a way of determining the value at a node, an initial node generator, a neighbor generator, and a way of determining the highest valued neighbor.

Starting with the way of determining the value at a node, it's very intuitive: calculate the value $z = f(x, y)$.

class HillClimber:

"""A steepest-ascent hill-climbing algorithm."""

def __init__(self, function):

self.function = function

def _value_at_node(self, node):

return self.function(node)

The initial node can simply be taken as a random $(x, y)$ in their respective bounds.

def _initial_node(self):

x = randint(self.function.x_bounds[0], self.function.x_bounds[1])

y = randint(self.function.y_bounds[0], self.function.y_bounds[1])

return Node(x, y)

Generating neighbors is actually quite simple as well: because our domain is limited to integers, we can simply look at the four cardinal directions (and make sure we won't be breaking the bounds when we do). Also, we randomize the neighbors, to make things more interesting[2].

def _generate_all_neighbors(self, node):

x, y = node.x, node.y

nodes = [Node(x, y)]

if x < self.function.x_bounds[1]:

nodes.append(Node(x + 1, y))

if x > self.function.x_bounds[0]:

nodes.append(Node(x - 1, y))

if y < self.function.y_bounds[1]:

nodes.append(Node(x, y + 1))

if y > self.function.y_bounds[0]:

nodes.append(Node(x, y - 1))

shuffle(nodes)

return nodes

Finally, to get the highest value node, it's fairly straightforward:

def _highest_valued_node(self, neighbors):

max_point = neighbors[0]

for point in neighbors[1:]:

if self._value_at_node(point) > self._value_at_node(max_point):

max_point = point

return max_point

Piecing all this together, we get our Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climber:

def climb(self):

current_node = self._initial_node()

while True:

print("Exploring Node({}, {})".format(current_node.x,

current_node.y))

neighbors = self._generate_all_neighbors(current_node)

successor = self._highest_valued_node(neighbors)

if (self._value_at_node(successor) <=

self._value_at_node(current_node)):

return current_node

current_node = successor

Does it work? Exactly as planned.

Exploring Node(5, -88)

...

Exploring Node(5, -67)

...

Exploring Node(5, -47)

...

Exploring Node(5, -27)

...

Exploring Node(5, -4)

Exploring Node(4, -4)

Exploring Node(3, -4)

Exploring Node(3, -3)

Exploring Node(2, -3)

Exploring Node(2, -2)

Exploring Node(1, -2)

Exploring Node(1, -1)

Exploring Node(1, 0)

Exploring Node(0, 0)

However, this was too easy. We had a function with one local optimum. Let's make things interesting.

Optimizing Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climbing

Suppose we keep our previous domain, but we change our function to the following:

$$

z = -(x^2 + y^2) + x\, y\, \cos x \sin y

$$

This function isn't quite as intuitive to visualize, please reference the figure. Essentially, it’s what we had before, but thousands of local optimum when we get further from the center. Our previous Hill-Climbing would absolutely get destroyed by that function.

To alleviate this, we are going to use two optimizations:

- Instead of taking the steepest uphill move, we are going to simply take a random, uphill move (known as Stochastic Hill-Climbing).

- When we get stuck, we are going to restart the search (known as Hill-Climbing With Restarts).

Stochastic Hill-Climbing

Updating the algorithm is fairly simply, all the previous mechanics are inheritable, just swap out _highest_valued_node with a stochastic version.

class StochasticHillClimber(HillClimber):

"""A stochastic steepest-ascent hill-climbing algorithm."""

def _get_random_uphill_move(self, current_node, neighbors):

uphill_nodes = []

for point in neighbors:

if self._value_at_node(point) > self._value_at_node(current_node):

uphill_nodes.append(point)

return current_node if len(uphill_nodes) == 0 else choice(uphill_nodes)

def climb(self):

current_node = self._initial_node()

while True:

print("Exploring Node({}, {})".format(current_node.x,

current_node.y))

neighbors = self._generate_all_neighbors(current_node)

successor = self._get_random_uphill_move(current_node,

neighbors)

if (self._value_at_node(successor) <=

self._value_at_node(current_node)):

return current_node

current_node = successor

Running this algorithm, we get better results; but we can do better.

Stochastic Hill-Climbing With Restarts

For this, we simply have to restructure the climb function to handle generational effects (like keeping the max valued node throughout generations). Not too difficult.

class StochasticHillClimberWithRestarts(StochasticHillClimber):

"""A stochastic steepest-ascent hill-climbing algorithm with restarts."""

def climb(self, number_of_generations):

max_node = self._initial_node()

for generations in range(number_of_generations):

current_node = self._initial_node()

while True:

msg = "Generation {}, Exploring Node({}, {}), " + \

"Current Max Node({}, {})"

print(msg.format(generations, current_node.x,

current_node.y,

max_node.x, max_node.y))

neighbors = self._generate_all_neighbors(current_node)

successor = self._get_random_uphill_move(current_node,

neighbors)

if (self._value_at_node(max_node) <

self._value_at_node(current_node)):

max_node = current_node

if (self._value_at_node(successor) <=

self._value_at_node(current_node)):

break

current_node = successor

return max_node

How did this one fare? Quite better than all the rest. Let's take a look at what the exploration process looked like.

Marvelous, some got to the top, many got caught in local optimum. A global-optimum was found. A success.

- Algorithms used in games, where a player searches for an optimal move against an opponent. ↩︎

- If the neighbors are always generated deterministically, there might occur a sequence of ties when generating the highest-valued node. We randomize the neighbors so a random piece will be chosen in the tie-breaker. ↩︎

This is an extension of a blog post I wrote a couple months ago. You can find it here.

One of the big takeaways in my introduction to Evolutionary Algorithms was the sheer number of numerical parameters.

- $\mu$ And $\lambda$

- Mutation Rate

- $k$ in k-Tournament Selection

Not only this, but the sheer number of parameters:

- The genotype

- The mutator operator

- The survivor selection algorithm

And one might be wondering, what is the best operator for $x$ or $y$? Let’s look at an example.

Recall the problem from the previous discussion: We are going to consider a sample problem, a deciphering program. The premise of the problem is as follows:

There is a string of characters (without spaces) hidden away that, after set, is inaccessible.

There are two ways to retrieve data about the hidden message:

1: Get the length of the string.

2: Given a string, the problem will output how many characters match within the two strings.

Disregarding the other technical details, let us focus on the survivor selection. We used $k$ -tournament selection (with $k = 50$). But, let’s run a little experiment:

Run the Evolutionary Algorithm, with $k$ ranging from $5$ (basically the bare minimum) to $100$ ($\lambda$, the population size), and see how fast the algorithm terminates. Do this 1,000 times to get accurate results.

The result?

This makes sense. Our problem has one local optimum: the actual solution. So we do not need a lot of genetic diversity, we need aggressive selective pressure[1] to reach the top quickly.

As $k$ gets closer to $\mu$, the average termination time decreases. What does this tell us? We picked the wrong survivor selection algorithm.

With $k = \mu$, we no longer have $k$ -tournament selection; we have truncation selection (where only the most fit individuals survive). And that's the interesting part about Evolutionary Algorithms: there are no objective, best parameters.

How do we alleviate this? Trial and error. There is no telling when one parameter is going to perform better than another.

After a couple of trial runs, and objectives in mind (average terminating fitness, best terminating fitness, time to termination), the answer might surprise (and delight) you.

- How elitist the survivor selection algorithm is, picking the strongest individuals more often. ↩︎

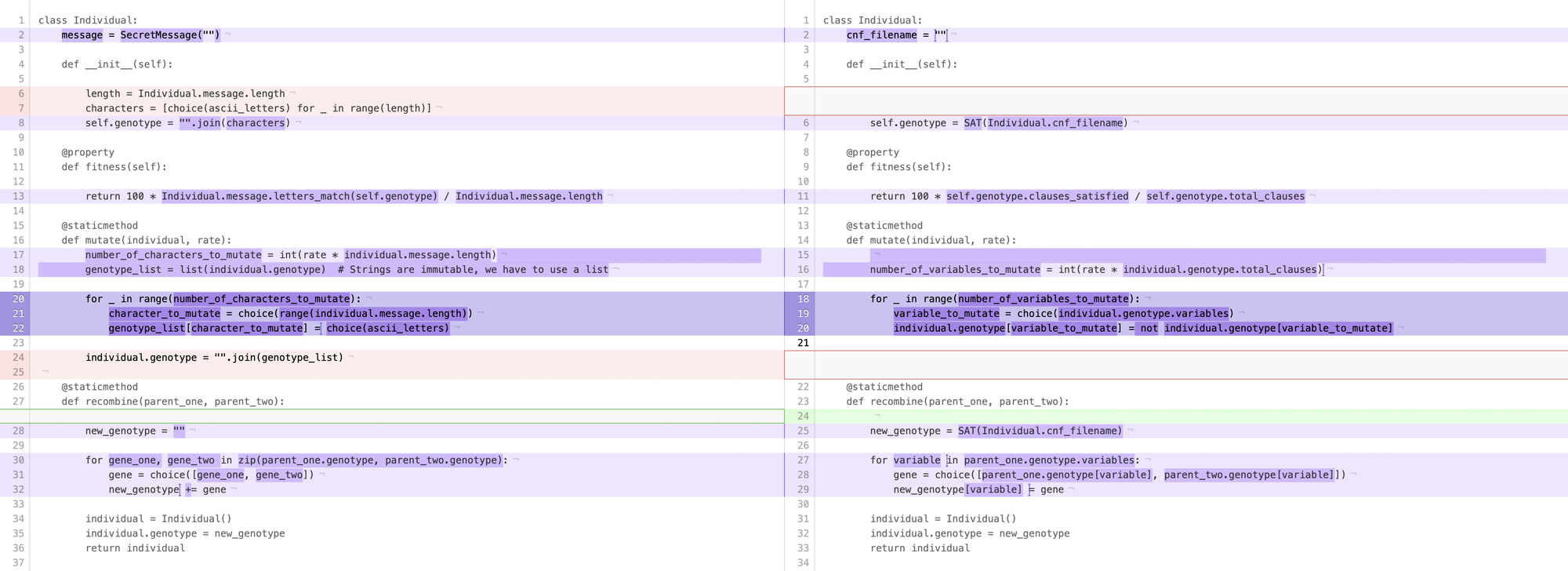

The Reusability Of Evolutionary Algorithms

3-SAT Solving With EAs

Let's propose an Evolutionary Algorithm experiment; say we already have a framework in place (like the Secret Message framework we previously implemented). How difficult would it be to completely switch problem instances?

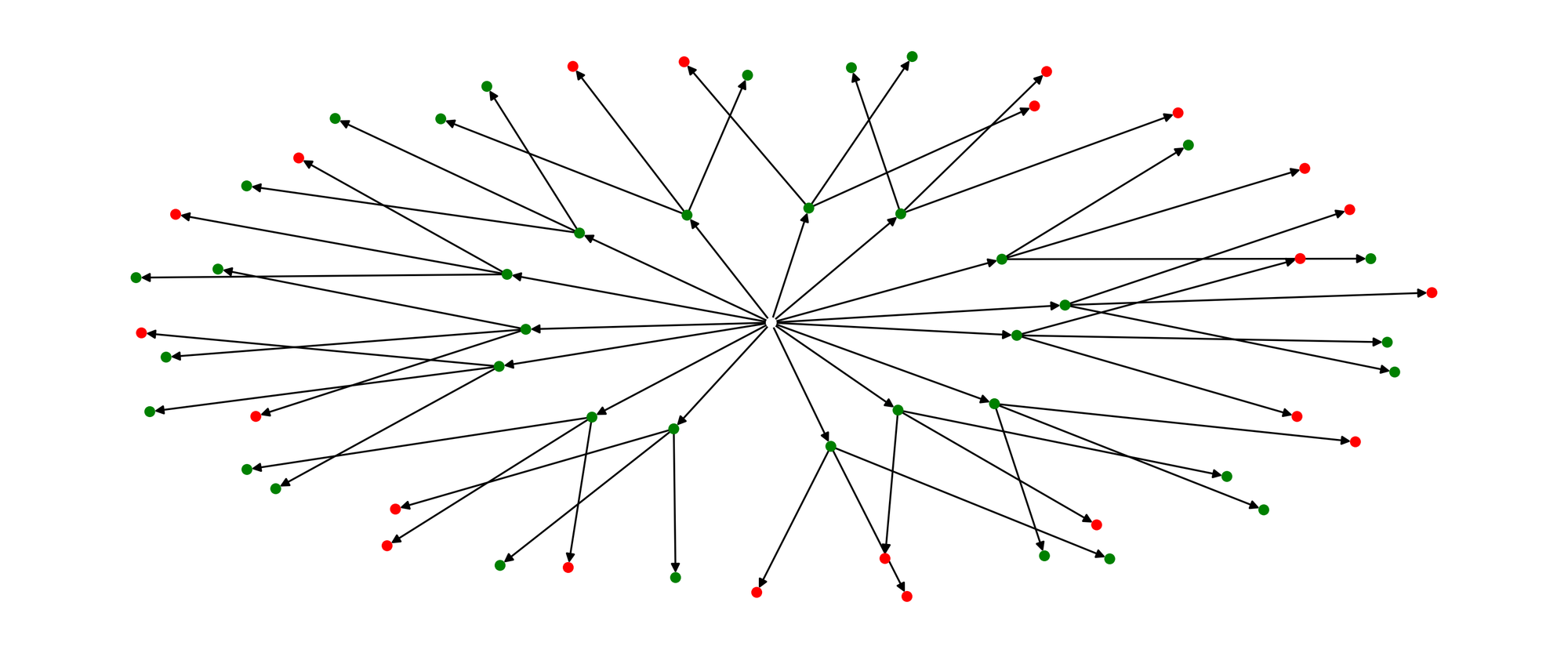

First, we need another problem instance. Our previous problem instance was pretty straightforward: it had one local optimum. Let's take on a problem with many local optima, such as the 3-SAT problem.

The premise of 3-SAT is simple. From a global pool of variables ($x_1$, $x_2$, $\ldots$, $x_n$), we have a basic clause of three variables or-ed together (signified by $\vee$):

$$x_p \vee x_q \vee x_r$$

Then, and (signified by a $\wedge$) several clauses together:

$$\left(x_p \vee x_q \vee x_r\right) \wedge \left(x_s \vee x_t \vee x_u\right) \wedge \ldots \wedge \left(x_v \vee x_w \vee x_y\right)$$

The only stipulation is that any variable can be negated (signified by a $\neg$). So, supposing we want to negate $x_p$; $x_s$ and $x_u$; and $x_v$, $x_w$, and $x_y$; we can do the following:

$$\left(\neg x_p \vee x_q \vee x_r\right) \wedge \left(\neg x_s \vee x_t \vee \neg x_u\right) \wedge \ldots \wedge \left(\neg x_v \vee \neg x_w \vee \neg x_y\right)$$

Now, we simply have to assign all the variables such that all the clauses will evaluate to true. It may sound simple, but it belongs to the hardest classes of problems in computer science. There is no guaranteed algorithm to produce the right answer at this time.

For a more visual approach, please reference the figure below. The goal is to make every inner node green, by having at least one connected outer node be green. Note the green nodes have to account for negation as well.

This sounds like a good problem candidate for an Evolutionary Algorithms.

The SAT Problem

We can skip over the problem specific parts to worry more about the Evolutionary Algorithm aspect. Suppose we already have a well-defined SAT class that takes care of SAT-specific properties and methods, like so:

class SAT:

def __init__(self, filename):

"""Create a SAT object that is read in from a CNF file."""

...

@property

def variables(self):

"""Get *all* the variables."""

...

@property

def total_clauses(self):

"""Get the total number of clauses."""

...

@property

def clauses_satisfied(self):

"""Get the number of satisfied clauses."""

...

def __getitem__(self, key):

"""Get a particular variable (key)"""

...

def __setitem__(self, key, value):

"""Set a variable (key) to value (True/False)"""

...

From this, we can create a new genotype for our Individual.

The New Genotype

The genotype structure was very similar to what we had before:

- The genotype is the

SATproblem we defined above. - Fitness is defined by a percentage of the total satisfied clauses.

- Mutation is uniform, choose a percentage $p$ of alleles and flip their value.

- Recombination is uniform, randomly assemble values from both parents.

Looking at the refactoring, not much has changed.

The New EA Framework

Now that we have updated our Individual, the next thing to update would be the Evolutionary Algorithm framework, including:

- The Population

- The EA Itself

Except, we don't have to.

That's the beauty of Evolutionary Algorithms, they are incredibly adaptable. By swapping out the Individual, the rest of the evolutionary algorithm should still work.

For our SAT problem, there were some parameters updated, to make the algorithm more efficient:

- The mutation rate has been reduced to 5%

- The tournament size has been reduced to 15 individuals (out of $\lambda = 100$).

The Result

So, let's try our Evolutionary Algorithm. Taking a SAT instance with 75 variables and 150 clauses, this makes the search space

$$2^{75} \approx 3.77 \times 10^{22}$$

Great, so roughly 1,000 times the grains of sand on Earth, easy. So, can our EA do it?

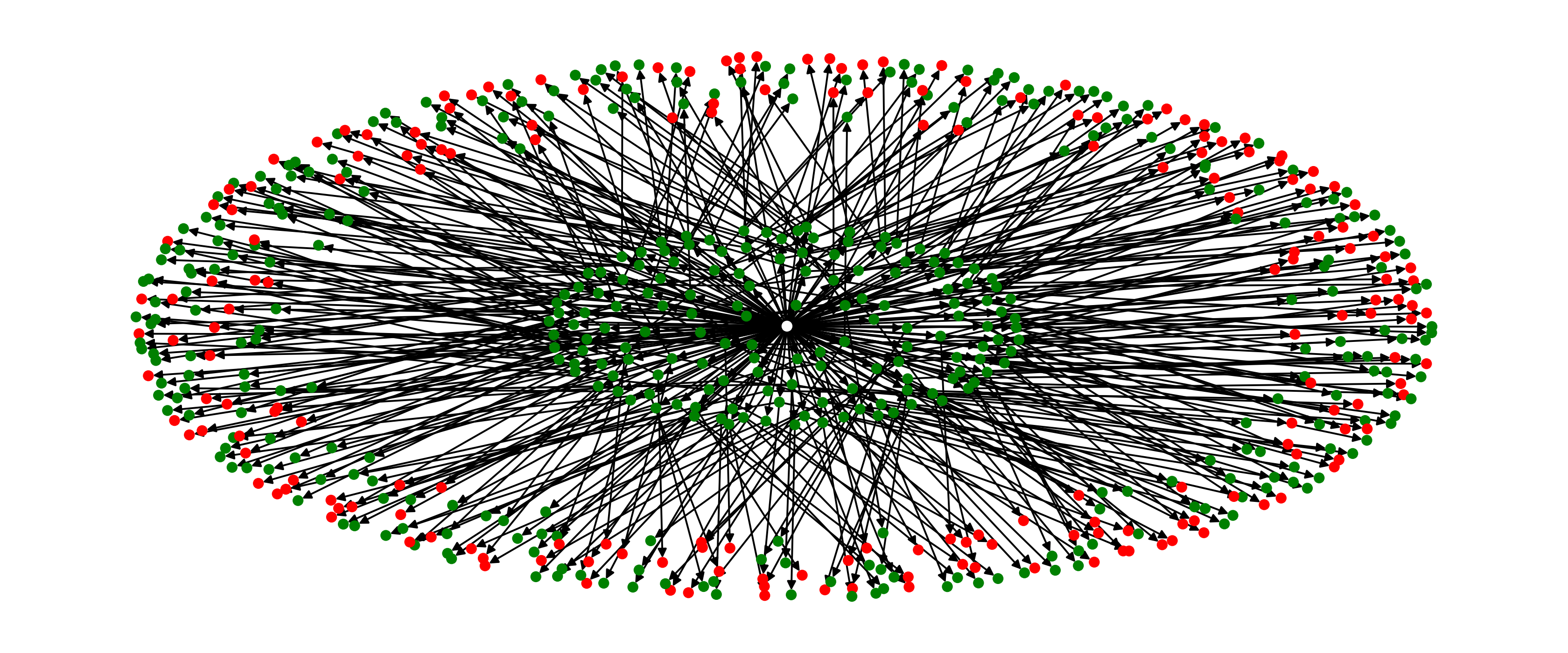

After roughly 100 iterations, yes. See the visualization below.

Marvelous, our EA managed to find a solution after only 100 iterations in a giant search space. And all we had to do was swap out one class.

Get to work. Grab a cup of coffee, some water. Possibly breakfast.

Sit down at my desk. Log into my computer, look at i3wm.

Launch a new terminal session. ranger. Enter. Navigate to project. nvim. Enter.

space f. Use fzf to open necessary file.

This is a daily workflow for me. Before I start typing code, I use about four tools to get to it. Notice, I haven’t mentioned touching the mouse once yet; Because I haven't touched the mouse yet.

Throughout my academic and professional career as a software engineer, I spent a lot of time using tools. Trying new tools. Searching for tools. Customizing tools[1].

Although this might be a commendable feat, it is often met with skepticism. A lot of skepticism.

I've had at least a hundred conversations with people about tools, about why they advocate against using such tools. These conversations were with other students, senior software engineers, and tenured professors—and generally, almost all of them fell into three distinct buckets of people.

It’s a waste of time.

This is by far the worst yet best counterargument against investing so heavily into tools—and the reasoning is in the trailing three words.

waste. Better tools will objectively help one write more code. If there is a modification that needs to be made at the end of the file, it takes one keystroke to jump to that position in Vim. Picture doing this, but 100s of times a day.

of time. There is a time commitment, a big one. And there is a learning curve, and it is steep. So, one would have to justify the reasons for learning it. And I've done so below.

What I have works just fine.

I’m deeply skeptical of the “If it’s not broken, don’t fix it” mentality. There’s always room for improvement, and there’s nothing more I love to see than improvement.

It’s why we buy new phones. It’s why we like nice, new cars. It’s why we, as civilization, love progress.

Even if it’s a marginal increase, say 5% more code a week. With a 100 lines of code written a week, that can be a about 250 additional lines of code written a year. A marginal increase, sure; but a welcomed one.

It doesn’t really make you a better programmer.

I generally have three core reasons against this, and they are as follows.

It'll help write more code, faster. It is objectively faster to type more code if your hands never leave the keyboard. It's faster to navigate a filesystem without having to focus on where a cursor is. It's ridiculously faster to open a file by just typing out parts of the filename as opposed to navigating to it.

It's healthier. Legitimately. Minimizing hand travel will significantly put less strain on your hands, wrists, and arms.

It'll make you a better programmer. As programmers, we have to learn things all the time. New programming languages, new paradigms, new company software. Learning a new tool keeps a mind sharp by reinforcing how to learn something. Plus, the skills are fluid. Learning to navigate in Vim will help navigate in ranger. Learning regular expressions can be used in fuzzy searches. The skills are transferable.

So, where might one start? Again, there are three areas I see that can have the most benefit from improving your workflow.

Your operating system. Whether it’s Windows, MacOS, or Linux, you have to use an operating system. Get good at it. Learn the paradigms of the system. Learn how the file explorer works in Windows. Learn advanced features in MacOS like a spotlight alternative or simple hot corners. Or learn how to set up your WiFi drivers in Linux.

Your text editor. Choose ones that are portable. I use NeoVim. Many people have success with Emacs. Some people prefer a visual editor like Sublime Text or Atom. Learn their workflows. Learn the shortcuts of Emacs. Learn how to edit text in Normal Mode using Vim. Install packages in Sublime or Atom. You spend most of your time here anyway, might as well get familiar with it.

The intermediary layer between your operating system and your text editor. By this, I usually mean the shell, like Bash or ZSH. Learn how to grep or navigate around. Install packages to make tasks easier. It’s well worth it.

So, yes, I am a strong advocate of using advanced tools. Established tools. Great tools. And I hope I’ve convinced you to do the same.

Arguably the first (and most successful) problem solver we know of is Evolution. Humans (along with other species) all share a common problem: becoming the best at surviving our environment.

Just as Darwinian finches evolved their beaks to survive different parts of the Galápagos Islands, we too evolved to survive different parts of the world. And we can program a computer to do the same.

Evolution inspired a whole generation of problem solving, commonly known as Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs). EAs have been known for solving (or, approximating) solutions to borderline unsolvable problems. And, just as the mechanics of evolution are not that difficult, the mechanics of EAs are just the same.

Today, we will build an Evolutionary Algorithm from the ground-up.

An Introduction

Before we proceed with implementation or an in-depth discussion, first we wish to tackle three questions: what is an Evolutionary Algorithm, what does an Evolutionary Algorithm look like, and what problems can Evolutionary Algorithms solve.

What Is An Evolutionary Algorithm?

An Evolutionary Algorithm is generic, population-based optimization algorithm that generates solution via biological operators. That is quite a mouthful, so let’s break it up.

Population-based. All Evolutionary Algorithms start by creating a population of random individuals. These individuals are just like an individual in nature: there is a genotype (the genes that make up an individual) and a phenotype (the result of the genotype interacting with the environment). In EAs, they would be defined as follows:

- Genotype The representation of the solution.

- Phenotype The solution itself.

Because it’s a little confusing to think of it this way, it’s often better to think about it in terms of a genotype space and a phenotype space.

- Genotype Space The space of all possible combinations of genes.

- Phenotype Space The space of all possible solutions.

Don’t worry if this doesn’t make sense, we’ll touch on it later.

Optimization Algorithm. Evolution is an optimization algorithm. Given an environment, it will try to optimize an individual for that environment with some fitness metric. Evolutionary Algorithms operate the same way.

Given an individual, it will try to optimize it. We do not use a literal environment, but still use a fitness metric. The fitness metric is simply a function that takes in the genotype of the individual, and outputs a value that is proportional to how good a solution is.

Because fitness metrics are proportional to how good a solution is, this implies a very important condition for our phenotype space: it’s a gradient.