Mathematics

We are well aware of Euler’s famous number,

$$

e = 2.71828182845

$$

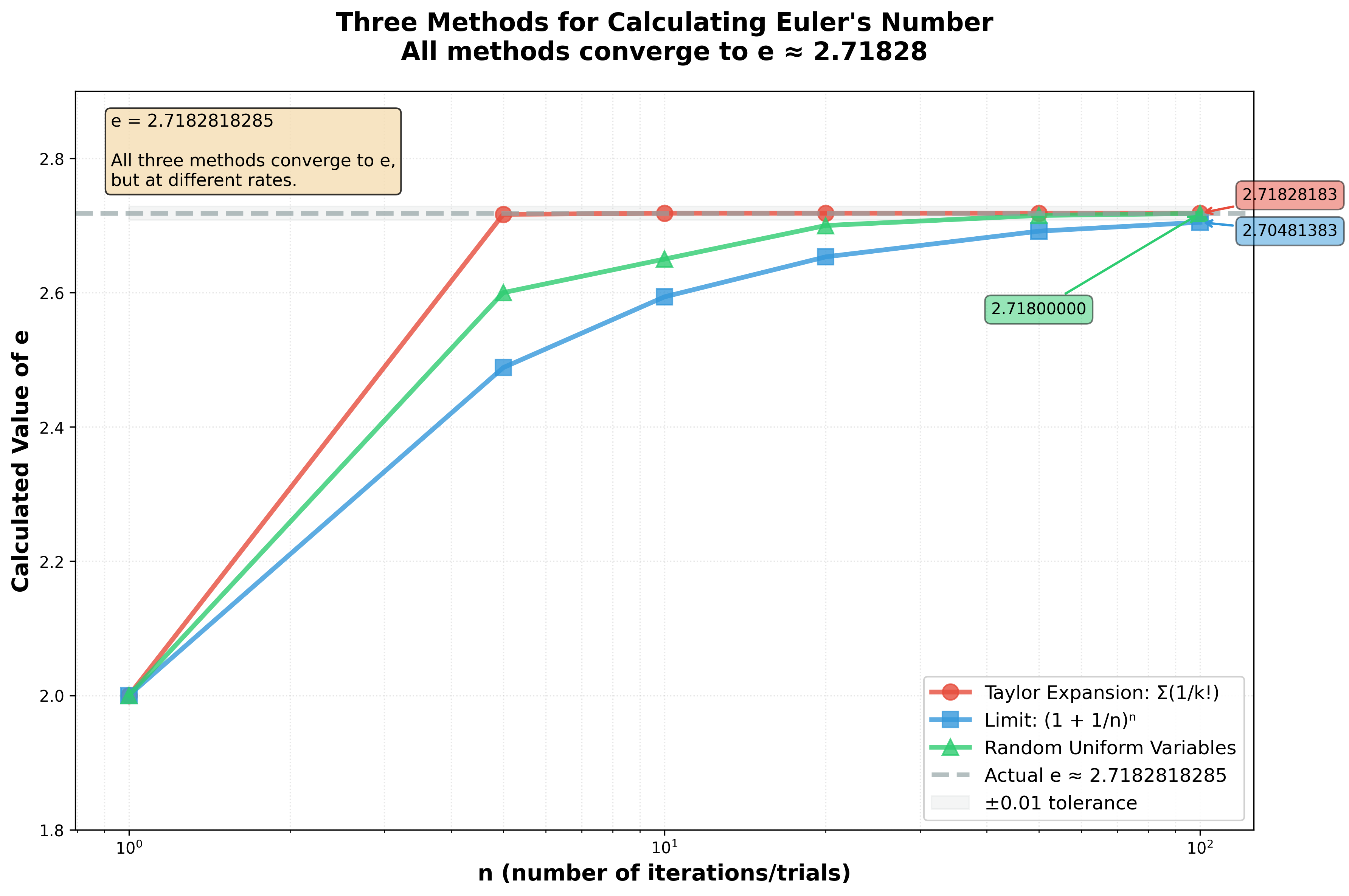

There are also quite a few ways of deriving Euler’s Number. There’s the Taylor expansion method:

$$

e = \sum _{k=0} ^{\infty} \frac{1}{k!}

$$

There is also the classical limit form:

$$

e = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \left( 1 + \frac{1}{n} \right)^n

$$

Then there is another. Let $R$ be a random number generated between $[0, 1]$, inclusive. Then $e$ is the average of the number of $R$s it takes to sum greater than $1$.

With more rigor, for uniform $(0,, 1)$ random independent variables $R_1$, $R_2$, $\ldots$, $R_n$,

$$

N = \min \left\{n: \sum_{k=1}^n R_k > 1 \right\}

$$

where

$$e = \text{Average}(n)$$

The proof can be found here, but it’s pretty math-heavy. Instead, an easier method is to write a program to verify for large enough $n$.

| n | Sum Solution | Limit Solution | Random Uniform Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | 1.7182818011 | 2.5937424601 | 2.5 |

| 100 | 1.7182818284 | 2.7048138294 | 2.69 |

| 1000 | 1.7182818284 | 2.7169239322 | 2.717 |

| 10000 | 2.7181459268 | 2.7242 | |

| 100000 | 2.7182682371 | 2.71643 | |

| 1000000 | 2.7182804690 | 2.71961 | |

| 10000000 | 2.7182816941 | 2.7182017 | |

| 100000000 | 2.7182817983 | 2.71818689 | |

| 1000000000 | 2.7182820520 | 2.718250315 |

Source Code

def e_sum(upper_bound):

if upper_bound < 1:

return 0

return Decimal(1.0) / Decimal(math.factorial(upper_bound)) + \

Decimal(e_sum(upper_bound - 1))

def e_limit(n):

return Decimal((1 + 1.0 / float(n))**n)

def find_greater_than_one(value=0, attempts=0):

if value <= 1:

return find_greater_than_one(value + random.uniform(0, 1), attempts + 1)

return attempts

Throughout my undergraduate studies, I've become good at digging deeper until I completely understand a subject. But when I look around me, I realize I'm in the minority. Often, students only want to know how to get from question to answer without any intermediate thinking. I can't pinpoint a definitive reason why, but I have one hypothesis: encapsulation[1].

The most famous example I've encountered is the derivative of any trigonometric function besides $\sin x$ or $\cos x$. As any student who's taken Calculus can tell you,

$$\frac{d}{dx} \left(\tan x\right) = \sec^2 x$$

However, most students couldn't tell you:

$$

\begin{align*}

\frac{d}{dx} \left(\tan x\right) &= \frac{d}{dx} \left(\frac{\sin x}{\cos x}\right) \\

&= \frac{\cos x \cos x + \sin x \sin x}{\cos^2 x} \\

&= \frac{\cos^2 x + \sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x} \\

&= \frac{1}{\cos^2 x} \\

&= \sec^2 x

\end{align*}

$$

At first glance, this seems like useless information. You might even think of it as a piece of trivia—until you see how many people miss it on a quiz or test. And entry-level Calculus isn't the only place this matters. This pattern appears everywhere: physics, thermodynamics, mathematics of any kind, computer science, and the like.

You might be wondering: why does it matter? If it's worth a couple of points on a test, is it that harmful? Maybe not—until you realize you don't conceptually understand the subject, only mechanically.

The next time you're learning something, ask yourself: "why?". The outcome might delight you.

- The act of enclosing in a capsule; the growth of a membrane around (any part) so as to enclose it in a capsule. ↩︎

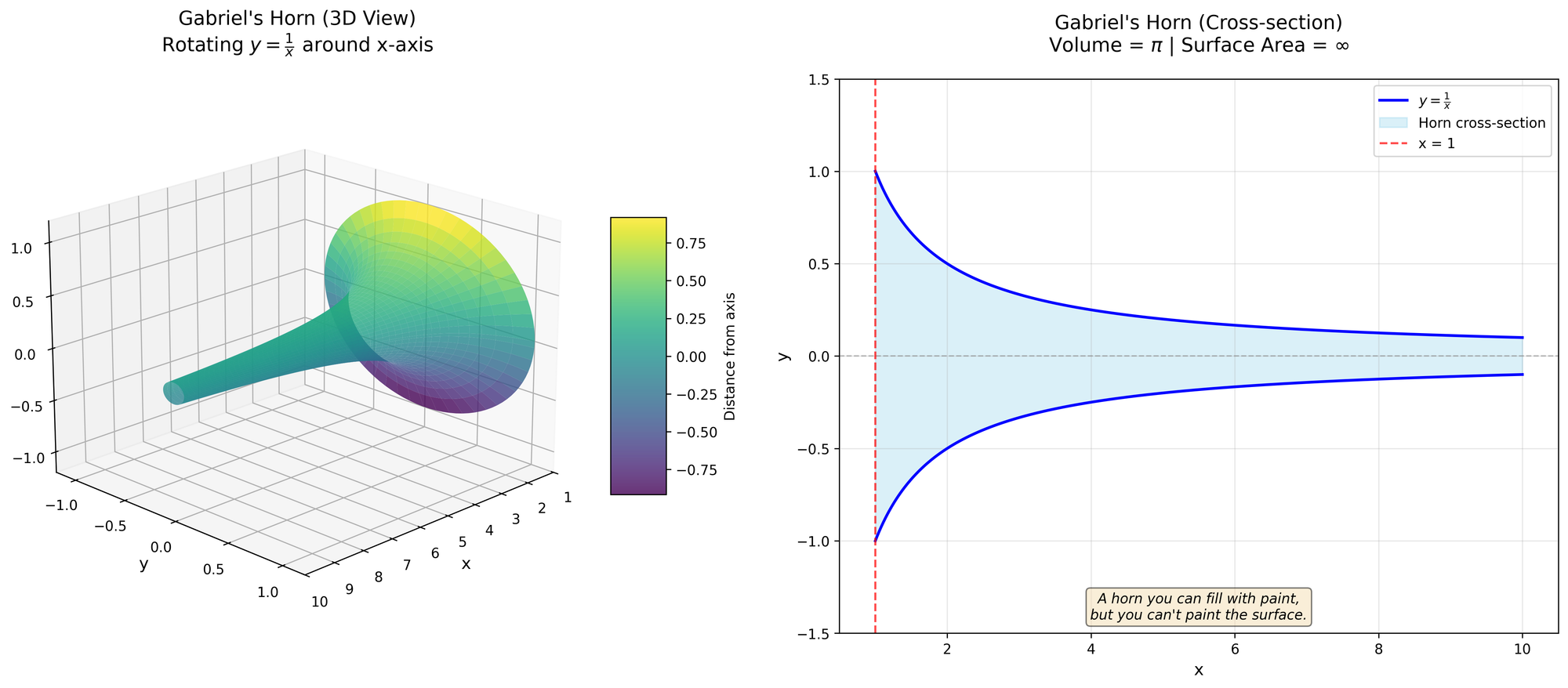

Painting Gabriel’s Horn

A horn you can fill with paint, but you can't paint the surface.

Mathematics is full of wonderful things, but nothing strikes me as more wonderful—or more unintuitive—than Gabriel's Horn.

Here's how it works: take the function $y = \frac{1}{x}$ where $x \in \mathbb{R}^+, 1 \leq x \leq \infty$, and rotate it around the $x$ axis. Not too hard to picture—it looks like a horn. But here's where it gets weird.

Let's calculate the volume. Using solids of revolution, we can show:

$$

V = \pi \lim_{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{1}{x^2} dx = \pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} ( 1 - \frac{1}{t} ) = \pi

$$

Simple, elegant. The volume is exactly $\pi$. Now let's check the surface area.

We know the general definition of arc length is $\int _a ^b \sqrt{1 + f'(x)^2}$. Combining this with our solids of revolution gives us:

$$

A = 2\pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{1}{x} \sqrt{1 + \left( -\frac{1}{x^2} \right)^2 } dx

$$

This integral isn't trivial, but there's a trick. Take the simpler integral $$2\pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{dx}{x}$$ instead. This will always be less than or equal to our original integral (we dropped the $\sqrt{1 + (-\frac{1}{x2})2}$ term, which is always ≥ 1). Evaluating this simpler integral:

$$

A \geq 2\pi \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} \int _1 ^t \frac{dx}{x} \implies A \geq \lim _{t \rightarrow \infty} 2\pi \ln(t)

$$

Wait. It diverges. The volume is $V = \pi$, but the surface area is $A \geq \infty$. This isn't a mistake—the math checks out. And that's simply wonderful.

A horn you can fill with paint, but you can't paint the surface.

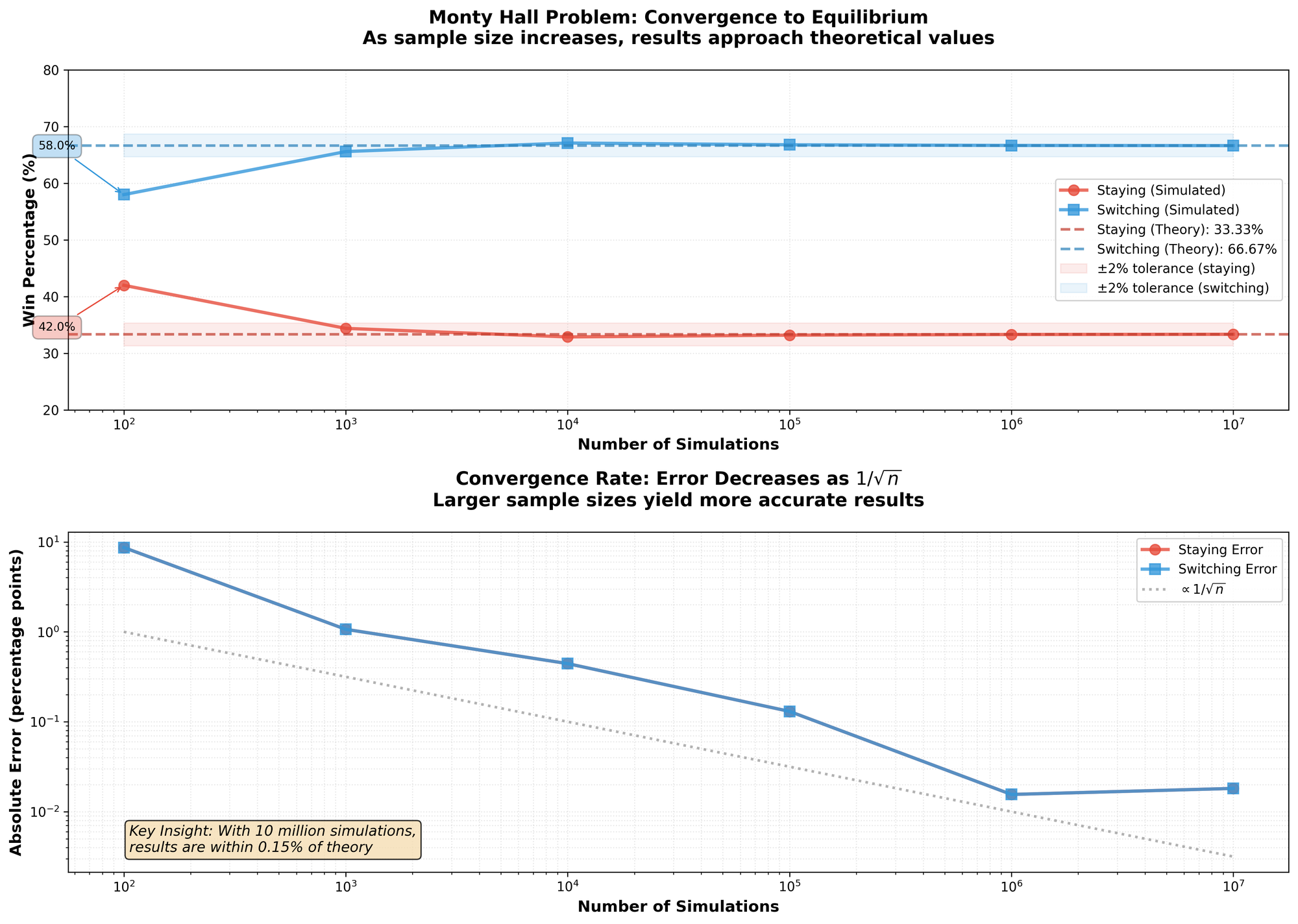

The Monty Hall Problem

You've seen it in movies or read about it in books: the Monty Hall Problem. Here's how it works: you're on a game show. There are three doors—behind one is a prize, behind the other two is nothing but disappointment. You pick a door. The host, Monty Hall, opens one of the other doors and reveals there's no prize behind it. Keeping the other two doors closed, he asks if you'd like to switch your choice or stick with your original pick. What should you do? Ben Campbell has a solution.

You mean to tell me that switching mid-game—an offer from the man who set up all the doors and prizes—gives me better odds of winning? How is this possible? Seems a bit counterintuitive. Seems almost wrong. Fortunately, we can test this with a simple program.

import Darwin // for arc4random_uniform

func random(from from: Int, to: Int,

except: Array<Int>? = nil) -> Int {

// Produce bounds, +1 to make inclusive

let number = Int(arc4random_uniform(UInt32(to - from + 1))) + from

if except != nil && except?.indexOf(number) != nil {

// Recursively call until we find a valid number

return random(from: from, to: to, except: except)

}

return number

}

// Returns if you won when you stayed and switched, respectively

func montyHall(doors: Int) -> (Bool, Bool) {

let originalDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors)

let correctDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors)

// The door the host reveals

let revealedDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors,

except: [correctDoor, originalDoor])

// If you switched, this would be your new door

let switchedDoor = random(from: 1, to: doors,

except: [revealedDoor, originalDoor])

return (originalDoor == correctDoor, switchedDoor == correctDoor)

}

let testValues = [100, 1_000, 10_000, 100_000,

1_000_000, 10_000_000]

let actualNumberOfDoors = 3

for value in testValues {

var stayingCounter = 0, switchingCounter = 0

for _ in 0...value {

let (stayedWon, switchedWon) = montyHall(actualNumberOfDoors)

if stayedWon { stayingCounter += 1 }

if switchedWon { switchingCounter += 1 }

}

let output = "Test Case: \(value). " +

"Staying Won: \(stayingCounter), " +

"Switching Won: \(switchingCounter)"

print(output)

}

There's no tricks in the code. No gimmicks. So, the results?

| Input | Staying Won | Switching Won |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 42 | 58 |

| 1000 | 344 | 656 |

| 10000 | 3289 | 6711 |

| 100000 | 33203 | 66797 |

| 1000000 | 333178 | 666822 |

| 10000000 | 3335146 | 6664854 |

It appears that Ben[1] was right. Taking the limit as the input gets higher, switching won roughly $66%$ of the time—compare that to the original $33%$ you got before you were given the option to switch doors. So, how is this possible? I'll explain.

For simplicity, suppose the prize is behind door A out of doors A, B, C. The argument can be made for any initial door, but A makes it easier. At this point, you have a $\frac{1}{3}$ chance of picking the prize no matter what you pick. If you pick door A, the door which contains the prize, the host will definitely want you to change so he will offer you either door B or C. Now suppose you choose a door without the prize, either door B or C. The host has no choice but to eliminate the door without the prize. Meaning if you switch, you have the winning door.

So, why $66%$? Computationally, if you always switch and you picked the wrong door initially, your switch will win every time. There are two incorrect choices out of three, meaning $\frac{2}{3}$ of the time you will win.

You've just had your first lesson in conditional probability.

- 21 main character, played by Jim Sturgess ↩︎